These vintage photos, taken by Sten-Åke Stenberg, depict the street scenes and everyday life in the Soviet Union in the early 1970s.

The Soviet 1970s was long. Coinciding with the rule of Leonid Brezhnev from 1964 to 1982 in both scholarly and popular understanding, the period is associated with a variety of concepts—“developed socialism,” “mature socialism,” “re-Stalinization,” and, most often, “stagnation.”

But as many scholars of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe are increasingly noting, the 1970s as a period of stagnation is too simple.

It was a time of profound change and globalization, even for state socialist societies. Life behind the Iron Curtain began resembling life on the other side—a complex, modern post-industrial consumerist society.

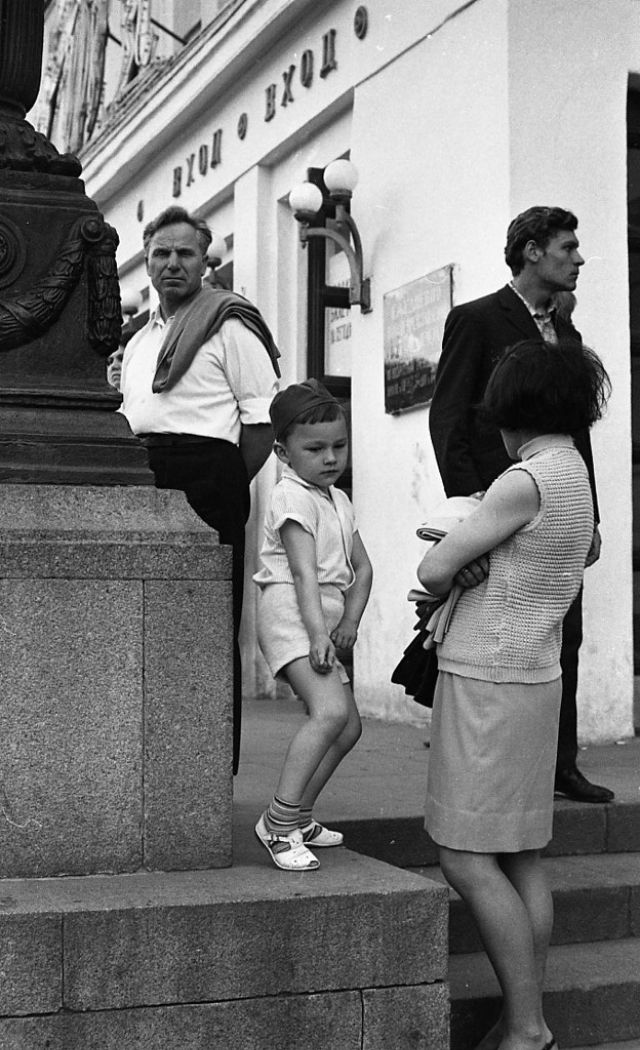

Moscow, 1971.

The 1965 Soviet economic reform, often referred to as the “Kosygin reform”, of economic management and planning was carried out between 1965 and 1971.

Announced in September 1965, it contained three main measures: the re-centralization of the Soviet economy by re-establishing several central ministries, a decentralizing overhaul of the enterprise incentive system (including wider usage of capitalist-style material incentives for good performance), and thirdly, a major price reform.

Though these measures were established to counter many of the irrationalities in the Soviet economic system, the reform did not try to change the existing system radically; it instead tried to improve it gradually.

Success was ultimately mixed, and Soviet analyses on why the reform failed to reach its full potential have never given any definitive answers.

The key factors are agreed upon, however, with blame being put on the combination of the decentralization of the economy with the decentralization of enterprise autonomy, creating several administrative obstacles.

Moscow, 1971.

The Era of Stagnation (1964-1982), a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, is considered by several economists to be the worst financial crisis in the Soviet Union.

It was triggered by the Nixon Shock, over-centralization, and a conservative state bureaucracy. As the economy grew, the volume of decisions facing planners in Moscow became overwhelming.

As a result, labor productivity decreased nationwide. The cumbersome procedures of bureaucratic administration did not allow for the free communication and flexible response required at the enterprise level to deal with worker alienation, innovation, customers, and suppliers. The late Brezhnev Era also saw an increase in political corruption

Leningrad park, 1971.

With the mounting economic problems, skilled workers were usually paid more than had been intended in the first place, while unskilled laborers tended to turn up late, and were neither conscientious nor, in a number of cases, entirely sober.

The state usually moved workers from one job to another which ultimately became an ineradicable feature in Soviet industry; the Government had no effective counter-measure because of the country’s lack of unemployment.

Government industries such as factories, mines, and offices were staffed by undisciplined personnel who put a great effort into not doing their jobs. This ultimately led to, according to Robert Service, a “work-shy workforce” among Soviet workers and administrators.

Leningrad street scenes, 1971.

Kosygin initiated the 1973 Soviet economic reform to enhance the powers and functions of the regional planners by establishing associations.

The reform was never fully implemented; indeed, members of the Soviet leadership complained that the reform had not even begun by the time of the 1979 reform. The 1979 Soviet economic reform was initiated to improve the then-stagnating Soviet economy.

The reform’s goal was to increase the powers of the central ministries by centralizing the Soviet economy to an even greater extent. This reform was also never fully implemented, and when Kosygin died in 1980 it was practically abandoned by his successor, Nikolai Tikhonov.

Tikhonov told the Soviet people at the 26th Party Congress that the reform was to be implemented, or at least parts of it, during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985).

Despite this, the reform never came to fruition. The reform is seen by several Sovietologists as the last major pre-perestroika reform initiative put forward by the Soviet government.

Moscow, 1971.

Leningrad, 1971.

Leningrad. Decembrists’ Square (now Senate Square). Building of the Senate and Sinode at the right, 1971.

Leningrad. Hotel Spotnik, 1971.

Leningrad. Women speaking at the street corner, 1971.

Moscow Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, 1971.

Moscow Metro, 1971.

Moscow Metro, 1971.

Moscow park, 1971.

Moscow street scenes, 1971.

Moscow. A restaurant, 1971.

Moscow. Boy on a bicycle, 1971.

Moscow. Cleaning the Red Square, 1971.

Moscow. Exhibition of Soviet Economic Achievements. Building in the background is a pavilion of a coal industry, 1971.

Moscow. Fruit shop, 1971.

Moscow. Man sitting on a bench reading the paper, 1971.

Moscow. Mother and son, 1971.

Moscow. Old lady, 1971.

Moscow. Road workers, 1971.

Moscow. Soviet family, 1971.

Moscow. Soviet ice cream, 1971.

Moscow. Soviet poster about a war movie, 1971.

Moscow. The main entrance to the Exhibition of Soviet Economic Achievements, 1971.

Moscow. Water machine, 1971.

Novgorod, 1971.

Novgorod. Babushkas, 1971.

Leningrad, 1973.

Leningrad, 1973.

Leningrad. A girl with her dog, 1973.

Leningrad. Nevsky Prospect, 1973.

Moscow, 1973.

Moscow. A family, 1973.

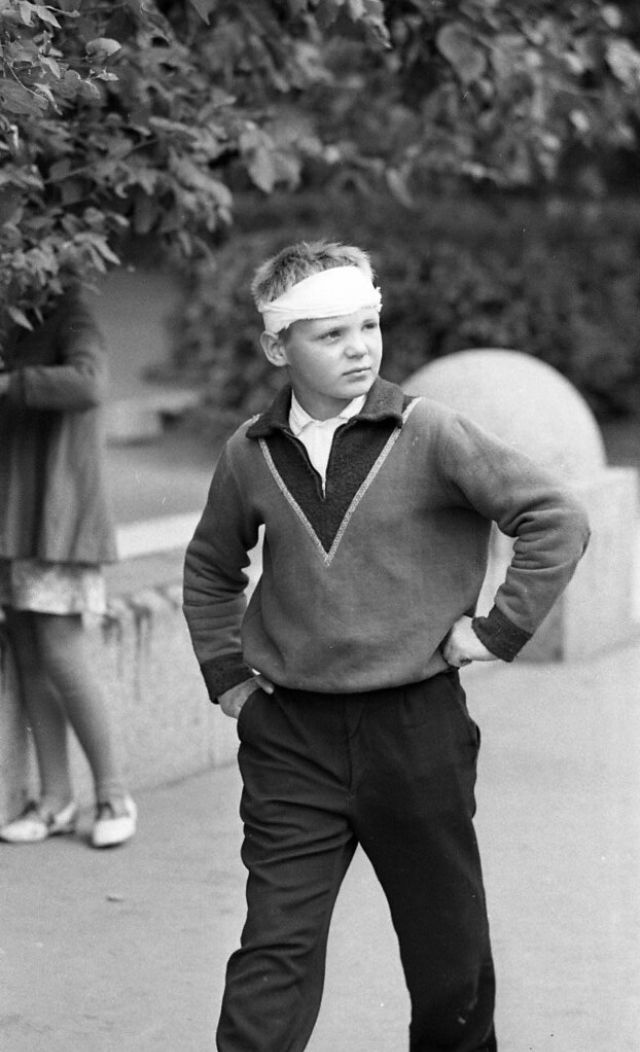

Moscow. Boy with a rifle, 1973.

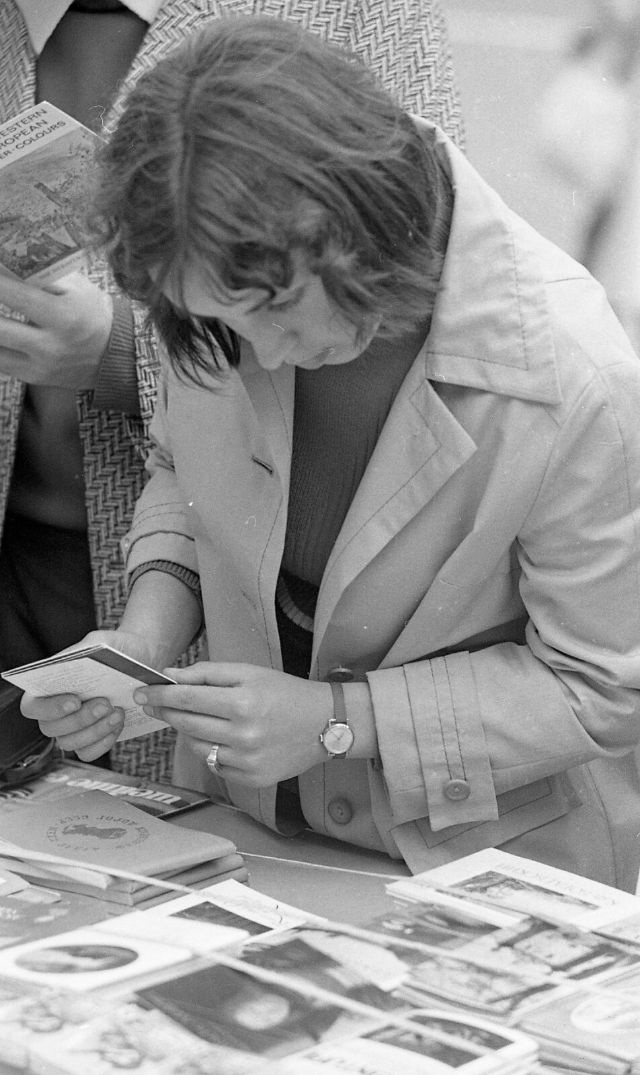

Moscow. Girl and books, 1973.

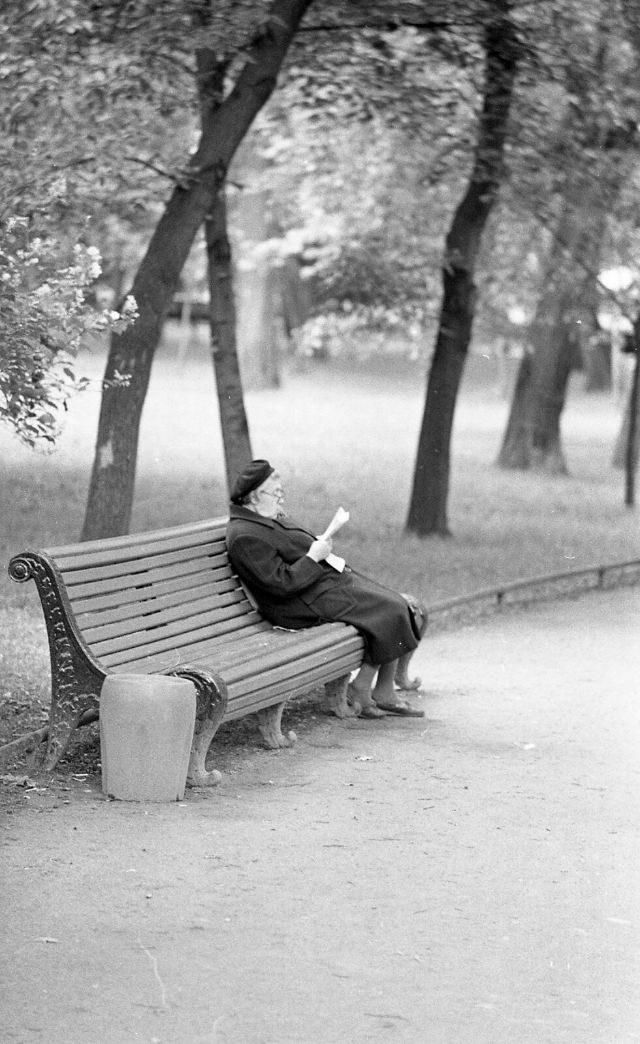

Moscow. Lady reading on a bench, 1973.

Moscow. Old lady, 1973.

(Photo credit: Sten-Åke Stenberg / Flickr / Wikimedia Commons).