While the First World War witnessed the development of modern, technological warfare, it also made unprecedented demands on what we might see as archaic methods of campaigning.

Despite the tanks, planes, and machine guns, fighting still depended on the physical and emotional suffering and sacrifice of men, who also had to contend with mud, sand, water, disease, and often brutal weather.

Moreover, like fighting men since time immemorial, the armies of the Allies and the Central Powers depended on the efforts and skills of animals for transport, logistics, communications, and, at times, solace.

The extent of the logistical apparatus that made the war feasible is almost impossible to imagine. Today, hundreds of tons of armaments remain to be discovered under the former battlefields of Belgium and France.

The numbers and weights involved are vast: during the Battle of Verdun, for example, some 32 million shells were fired, while the British barrage preceding the Battle of the Somme fired some 1.5 million shells (in total, nearly 250 million shells were used by the British army and navy during the war).

Gas attack on the West Front, near St. Quentin 1918—a German messenger dog loosed by his handler. Dogs were used throughout the war as sentries, scouts, rescuers, messengers, and more.

Railways, trucks, and ships transported these munitions for much of their journey, but they also relied on hundreds of thousands of horses, donkeys, oxen, and even camels or dogs for their transport.

Field guns were pulled into position by teams of six to 12 horses, and the dead and wounded carted away in horse-drawn ambulances.

The millions of men at the front and behind the lines also had to be fed and supplied with equipment, much of which was again hauled by four-legged beasts of burden. Because of the deep mud and craters at the front, much of this could only be carried by mules or horses.

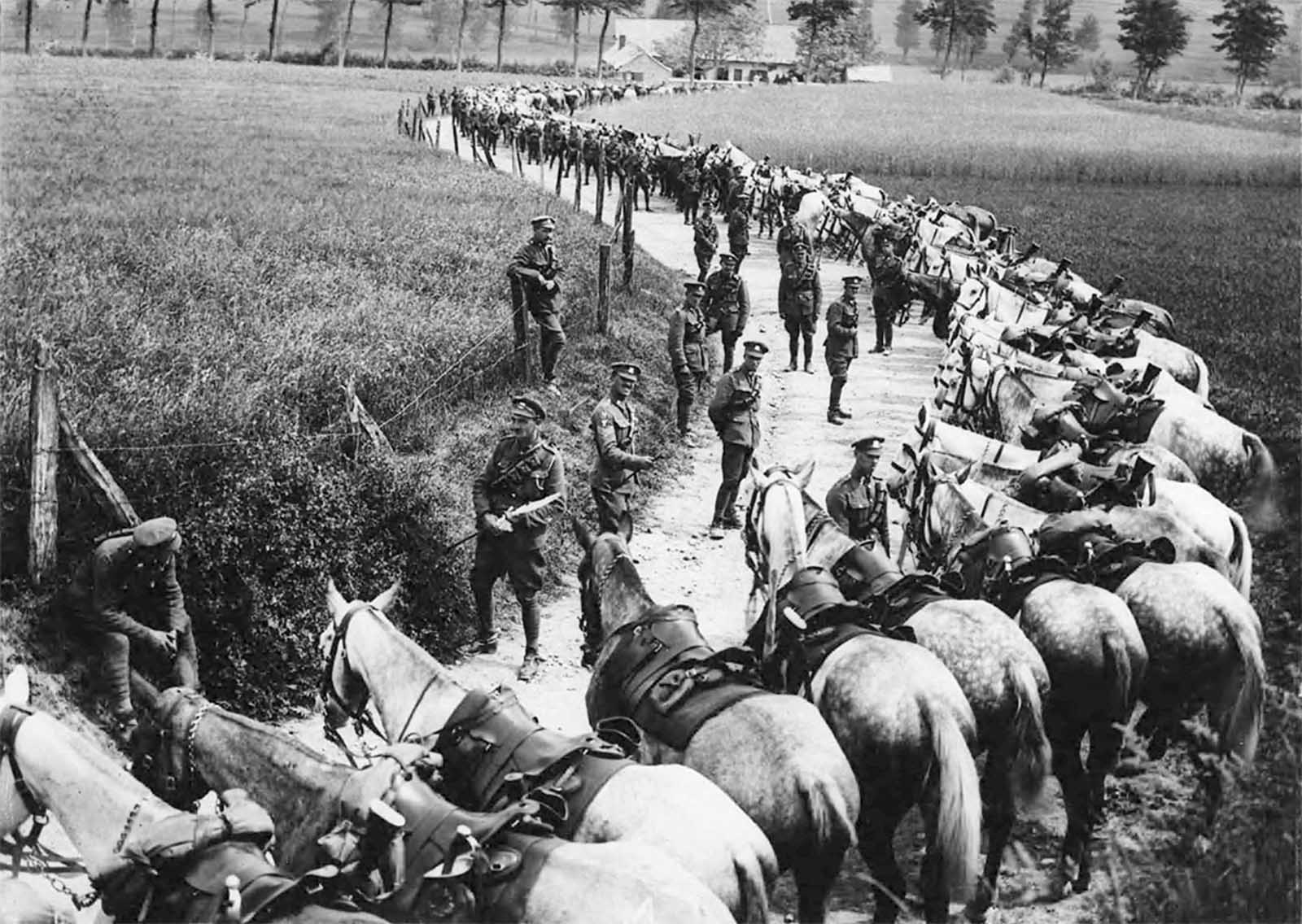

Even the British army, which could boast that it was the most mechanized of the belligerent forces, relied largely on horsepower for its transport, much of it organized by the Army Service Corps: by November 1918, the British army had almost 500,000 horses, which helped to distribute 34,000 tons of meat and 45,000 tons of bread each month.

German soldiers pose near a horse-mounted with a purpose-built frame, used to accommodate a captured Russian Maxim M1910 machine gun complete with its wheeled mount and ammunition box.

Bandages retrieved from the kit of a British Dog, ca. 1915.

The animals themselves needed feeding and watering, and British horses had to carry some 16,000 tons of forage each month. In total, perhaps six million horses were engaged by all sides.

Looking after these animals were specially trained soldiers, who knew how to care for such beasts from their jobs before the war, and who were also trained in modern methods of animal husbandry (although the level of training varied from army to army).

Without the millions of horses, mules, and donkeys serving on the various fronts, the war of attrition would have been impossible.

Losses through exhaustion, disease (such as infection from the tsetse fly in East Africa), starvation, and enemy action were high. 120,000 horses were treated in British veterinary hospitals in one year, many of which were field hospitals.

A pigeon with a small camera attached. The trained birds were used experimentally by German citizen Julius Neubronner, before and during the war years, capturing aerial images when a timer mechanism clicked the shutter.

The resupply of horses and other animals was a major concern for the leadership of all sides.

At the outbreak of the war, Britain’s horse population stood at under 25,000, and so it turned to the United States (which supplied around a million horses during the war), Canada, and Argentina.

Germany had prepared for war with an extensive breeding and registration program, and at the start of the war had a ratio of one horse to every three men.

However, while the Allies could import horses from America, the Central Powers could only replace their losses by conquest, and requisitioned many thousands from Belgium, from invaded French territory, and from Ukraine.

The difficulty of replacing horses arguably contributed to the eventual defeat of the Central Powers.

Unloading a mule in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1915. The escalating warfare drove Britain and France to import horses and mules from overseas by the hundreds of thousands. Vulnerable transport ships were frequent targets of the German Navy, sending thousands of animals to the bottom of the sea.

Despite the machine gun, barbed wire, and trenches (or thick bushes in the Levant), cavalry proved to be remarkably effective during the conflict where mobile fighting could take place.

Cavalry saw considerable action at Mons, and Russian cavalry penetrated deep into Germany during the early phases of the war. Cavalry was still occasionally used in their traditional role as shock troops even later in the war.

Cavalry was effective in Palestine, although were obstructed by thick bushes as much as by barbed wire.

Cavalrymen from Britain and her colonies were trained to fight both on foot and mounted, which perhaps accounts for horses’ more frequent use by these armies than by other European forces during the conflict.

But most military tacticians had already recognized that the importance of mounted soldiers had waned in the age of mechanized war, a shift that had already become apparent in the American Civil War.

Sergeant Stubby was the most decorated war dog of World War I and the only dog to be promoted to sergeant through combat. The Boston Bull Terrier started out as the mascot of the 102nd Infantry, 26th Yankee Division, and ended up becoming a full-fledged combat dog. Brought up to the front lines, he was injured in a gas attack early on, which gave him a sensitivity to gas that later allowed him to warn his soldiers of incoming gas attacks by running and barking. He helped find wounded soldiers, even captured a German spy who was trying to map allied trenches. Stubby was the first dog ever given rank in the United States Armed Forces, and was highly decorated for his participation in seventeen engagements, and being wounded twice.

Where cavalry regiments were maintained on the Western Front, many considered them a drain on men and resources, and futile in the face of machine guns.

This was despite the esteem in which such regiments were still held in the traditional military mind and the public popularity of the image of the dashing cavalryman.

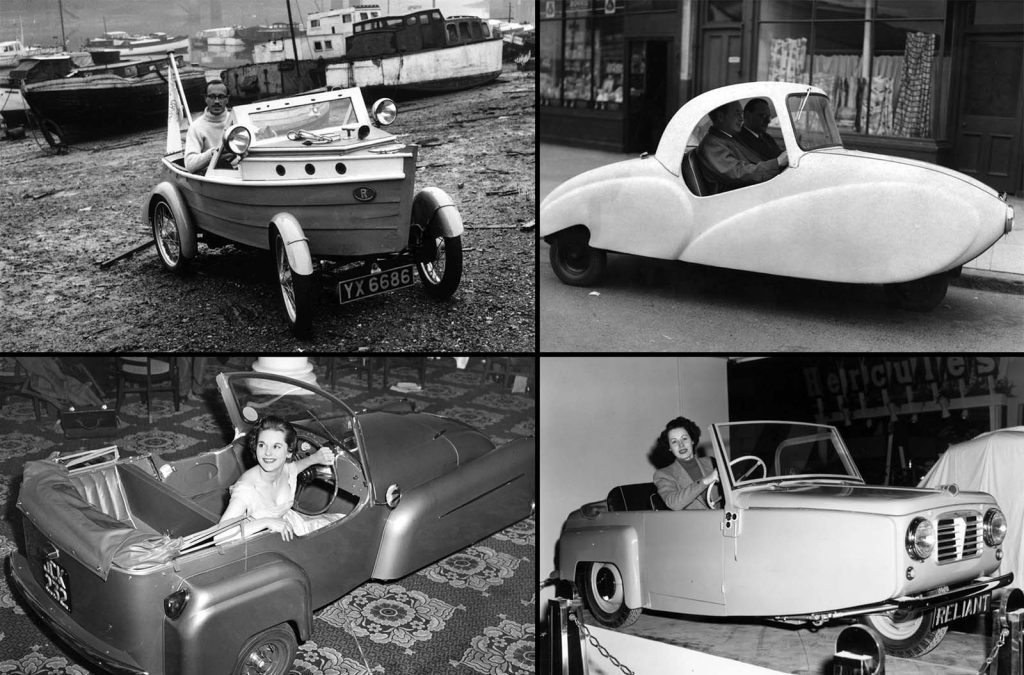

Members of the Royal Scots Greys cavalry regiment rest their horses by the side of the road, in France.

As well as acting as beasts of burden or participants in the fighting, animals also played a vital role in communication.

Trained dogs were used to carry messages from the front lines, especially by the German forces, and both sides made particularly heavy use of pigeons.

Trained birds, which could fly at 40kph or faster, relayed messages back from the front lines to headquarters, often more reliably or securely than telecommunications or radio.

Naval ships, submarines, and military airplanes routinely carried several pigeons to deploy in case of sinking or a crash landing.

Mobile homing pigeon units acted as communication hubs, and in Britain, pigeon fanciers assisted in breeding and training for the war effort. The French deployed some 72 pigeon lofts.

Pigeons also captured the popular imagination, with one American bird, ‘Cher Ami’, awarded a French medal for her service within the American sector near the town of Verdun.

On her last mission, she successfully carried her message, despite being shot through the chest, and purportedly saved the lives of 194 American soldiers with her news.

At Kemmel, West Flanders, Belgium. The effect of enemy artillery fire upon German ambulances, in May of 1918.

Animals also served important psychological functions during the war. The military had long had a close association with animals, either as symbols of courage (such as lions) or through the image of the warrior and his horse.

Similarly, the enemy could be depicted as an enraged beast, as Allied propaganda presented the German war machine.

The Central Powers reveled in depicting the British Empire as a duplicitous, colonizing ‘octopus’, an image that was in turn used against them by the French.

Regiments and other military groups often used animals as their symbol, emphasizing ferocity and bravery, and also adopted mascots, both as a means of helping to forge comradeship and to keep up morale.

A Canadian battalion even brought a black bear with them to Europe, which was given to the London Zoo, where the creature inspired the fictional character of Winnie the Pooh.

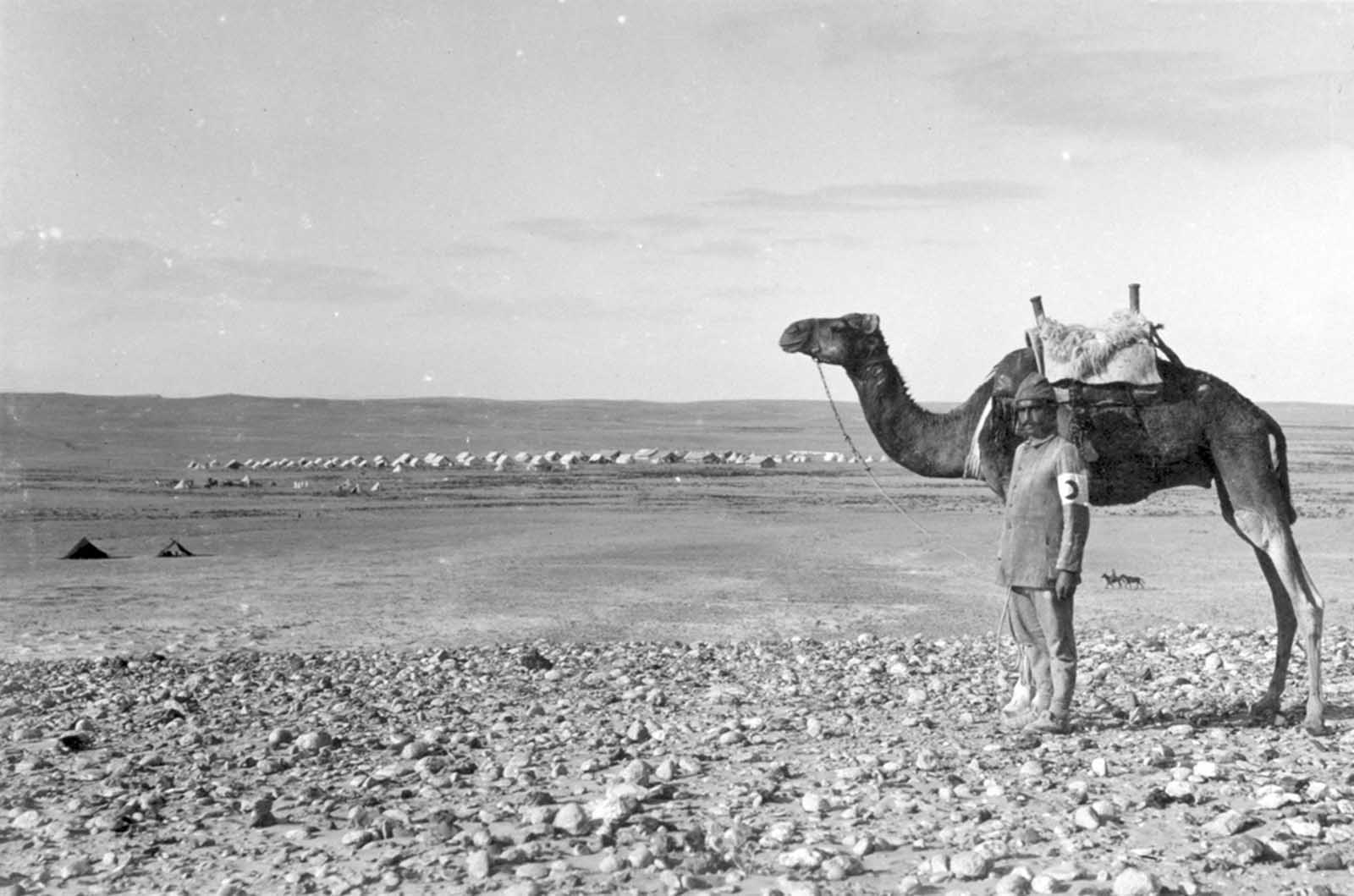

Red Crescent Hospital at Hafir Aujah, 1916.

There are many stories of the close relationship between men and their animals, whether bringing a reminder of a more peaceful life at home on the farm or as a source of companionship in the face of the inhumanity of man.

It is claimed that communications dogs were of little use among British soldiers, as they were petted too much and given too many rations from men in the trenches.

Close proximity also brought dangers to men at the front. Manure brought disease, as did the rotting bodies of dead horses and mules that could not be removed from the mud or no-man’s-land.

A corporal, probably on the staff of the 2nd Australian general hospital, holds a koala, a pet or mascot in Cairo, in 1915.

Animals at home also suffered. Many in Britain were killed in an invasion scare, and food shortages elsewhere led to starvation and death.

Lack of horses and other beasts of burden sometimes led to the ingenious use of circus or zoo animals, such as Lizzie the elephant, who did war service for the factories of Sheffield.

In total, World War I in which 10 million soldiers died, also resulted in the deaths of 8 million military horses.

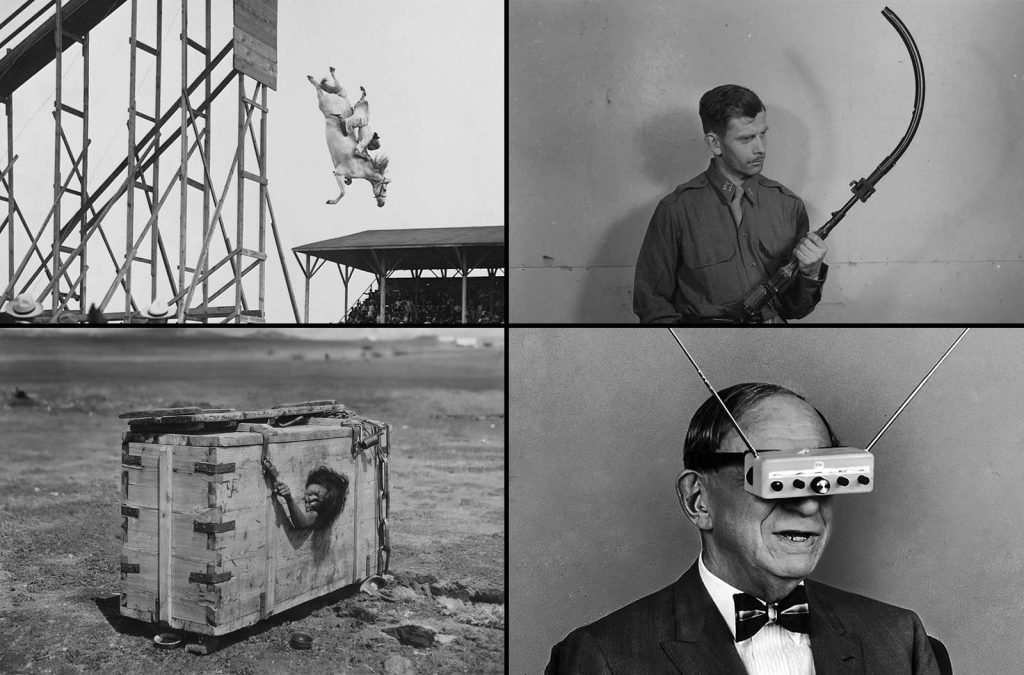

Turkish cavalry exercises on the Saloniki front, Turkey, March of 1917.

A messenger dog with a spool attached to a harness for laying out new electric line in September of 1917.

An Indian elephant, from the Hamburg Zoo, used by Germans in Valenciennes, France to help move tree trunks in 1915. As the war dragged on, beasts of burden became scarce in Germany, and some circus and zoo animals were requisitioned for army use.

German officers in an automobile on the road with a convoy of wagons; soldiers walk along side the road.

“These homing pigeons are doing much to save the lives of our boys in France. They act as efficient messengers and dispatch bearers not only from division to division and from the trenches to the rear but also are used by our aviators to report back the results of their observation”.

Belgian Army pigeons. Homing pigeon stations were set up behind the front lines, the pigeons themselves sent forward, to return later with messages tied to their legs.

Two soldiers with motorbikes, each with a wicker basket strapped to his back. A third man is putting a pigeon in one of the baskets. In the background there are two mobile pigeon lofts and a number of tents. The soldier in the middle has the grenade badge of the Royal Engineers over the chevrons which show he is a sergeant.

A message is attached to a carrier pigeon by British troops on the Western Front, 1917. One of France’s homing pigeons, named Cher Ami, was awarded the French “Croix de Guerre with Palm” for heroic service delivering 12 important messages during the Battle of Verdun.

A draft horse hitched to a post, its partner just killed by shrapnel, 1916.

The feline mascot of the light cruiser HMAS Encounter, peering from the muzzle of a 6-inch gun.

General Kamio, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Army at the formal entry of Tsing-Tau, December, 1914. The use of horses was vital to armies around the world during World War I.

Belgian refugees leaving Brussels, their belongings in a wagon pulled by a dog, 1914.

Australian Camel Corps going into action at Sharia near Beersheba, in December of 1917. The Colonel and many of these men were killed an hour or so afterward.

A soldier and his horse in gas masks, ca. 1918.

German Red Cross Dogs head to the front.

An episode in Walachia, Romania.

Belgian chasseurs pass through the town of Daynze, Belgium, on the way from Ghent to meet the German invasion.

The breakthrough west of St. Quentin, Aisne, France. Artillery drawn by horses advances through captured British positions on March 26, 1918.

Western Front, shells carried on horseback, 1916.

Camels line a huge watering station, Asluj, Palestinian campaign, 1916.

A British Mark V tank passes by a dead horse in the road in Peronne, France in 1918.

A dog-handler reads a message brought by a messenger dog, who had just swum across a canal in France, during World War I.

Horses requisitioned for the war effort in Paris, France, ca. 1915. Farmers and families on the home front endured great hardship when their best horses were taken for use in the war.

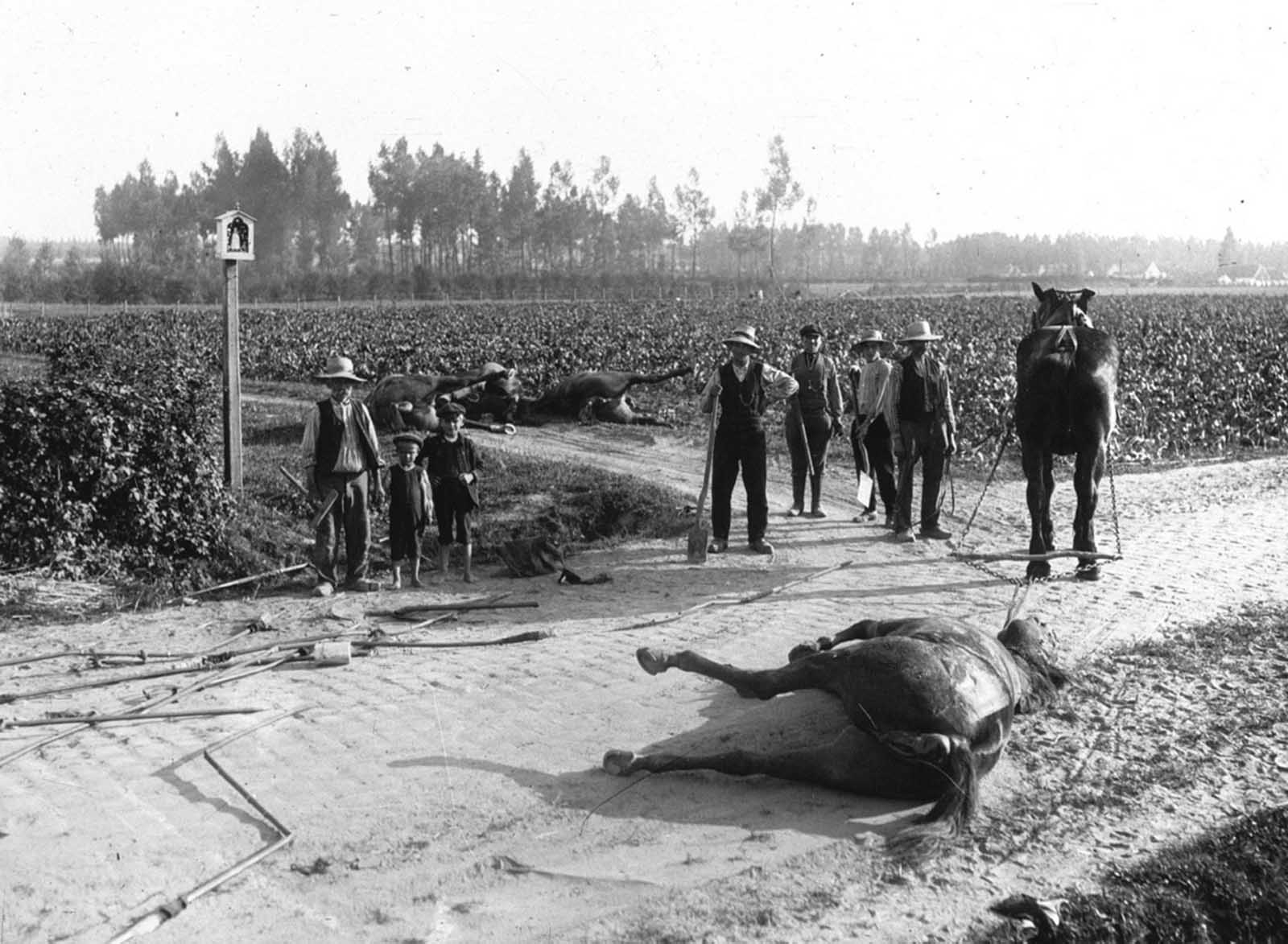

In Belgium, after the Battle of Haelen, a surviving horse is used in the removal of dead horses killed in the conflict, 1914.

A dog trained to search for wounded soldiers while under fire, 1915.

Algerian cavalry attached to the French Army, escorting a group of German prisoners taken in fighting in the west of Belgium.

A Russian Cossack, in firing position, behind his horse, 1915.

Serbian artillery in action on the Salonika front in December of 1917.

A horse strapped and being lowered into position to be operated on for a gunshot wound by 1st LT Burgett. Le Valdahon, Doubs, France.

6th Australian light-horse regiment, marching in Sheikh Jarrah, on the way to Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, in 1918.

French cavalry horses swim across a river in northern France.

Dead horses and a broken cart on Menin Road, troops in the distance, Ypres sector, Belgium, in 1917. Horses meant power and agility, hauling weaponry, equipment, and personnel, and were targeted by enemy troops to weaken the other side — or were captured to be put in use by a different army.

War animals carrying war animals — at a carrier pigeon communication school at Namur, Belgium, a dispatch dog fitted with a pigeon basket for transporting carrier pigeons to the front line.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Bundesarchiv / Bibliotheque Nationale de France / Text: Matthew Shaw).