The construction started in January 1887. The proposed tower had been a subject of controversy, drawing criticism from those who did not believe it was feasible and those who objected on artistic grounds.

In 1889, Paris hosted an Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) to mark the 100-year anniversary of the French Revolution. More than 100 artists submitted competing plans for a monument to be built on the Champ-de-Mars, located in central Paris, and serve as the exposition’s entrance.

The commission was granted to Eiffel et Compagnie, a consulting and construction firm owned by the acclaimed bridge builder, architect, and metals expert Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel.

While Eiffel himself often receives full credit for the monument that bears his name, it was one of his employees—a structural engineer named Maurice Koechlin—who came up with and fine-tuned the concept.

The assembly of the supports began on July 1, 1887, and was completed twenty-two months later. All the elements were prepared in Eiffel’s factory located at Levallois-Perret on the outskirts of Paris.

Each of the 18,000 pieces used to construct the Tower were specifically designed and calculated, traced out to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimeter, and then put together forming new pieces around five meters each.

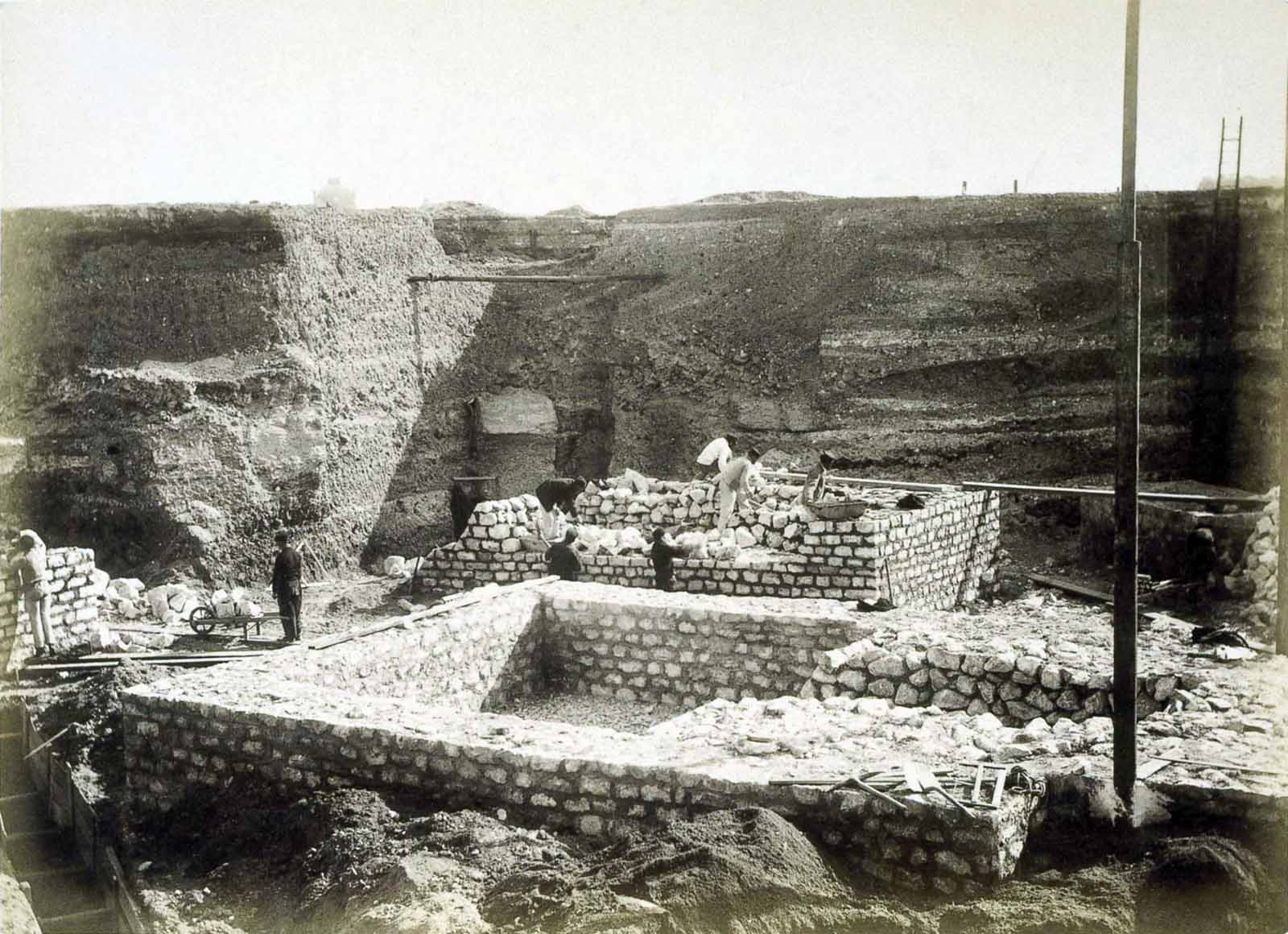

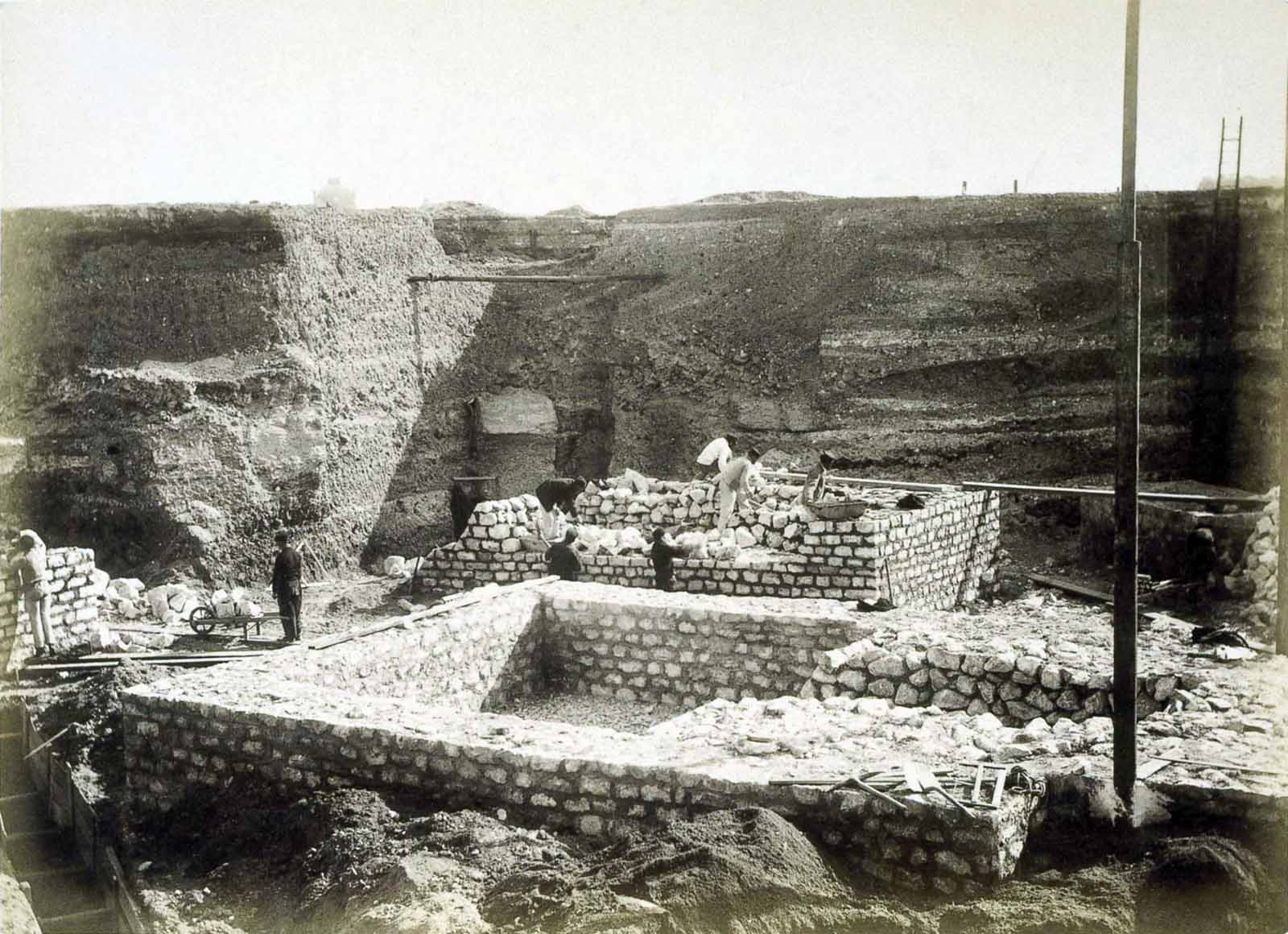

Foundations of the Eiffel Tower.

A team of constructors, who had worked on the great metal viaduct projects, were responsible for the 150 to 300 workers on-site assembling this gigantic erector set.

All the metal pieces of the tower are held together by rivets, a well-refined method of construction at the time the Tower was constructed.

First, the pieces were assembled in the factory using bolts, later to be replaced one by one with thermally assembled rivets, which contracted during cooling thus ensuring a very tight fit.

A team of four men was needed for each rivet assembled: one to heat it up, another to hold it in place, a third to shape the head and a fourth to beat it with a sledgehammer. Only a third of the 2,500,000 rivets used in the construction of the Tower were inserted directly on site.

One of the stone and cement foundations for the tower’s legs. April, 1887.

Workers prepare the foundation of the Eiffel Tower on April 25, 1887.

The uprights rest on concrete foundations installed a few meters below ground-level on top of a layer of compacted gravel. Each corner edge rests on its own supporting block, applying to it a pressure of 3 to 4 kilograms per square centimeter, and each block is joined to the others by walls.

On the Seine side of the construction, the builders used watertight metal caissons and injected compressed air, so that they were able to work below the level of the water.

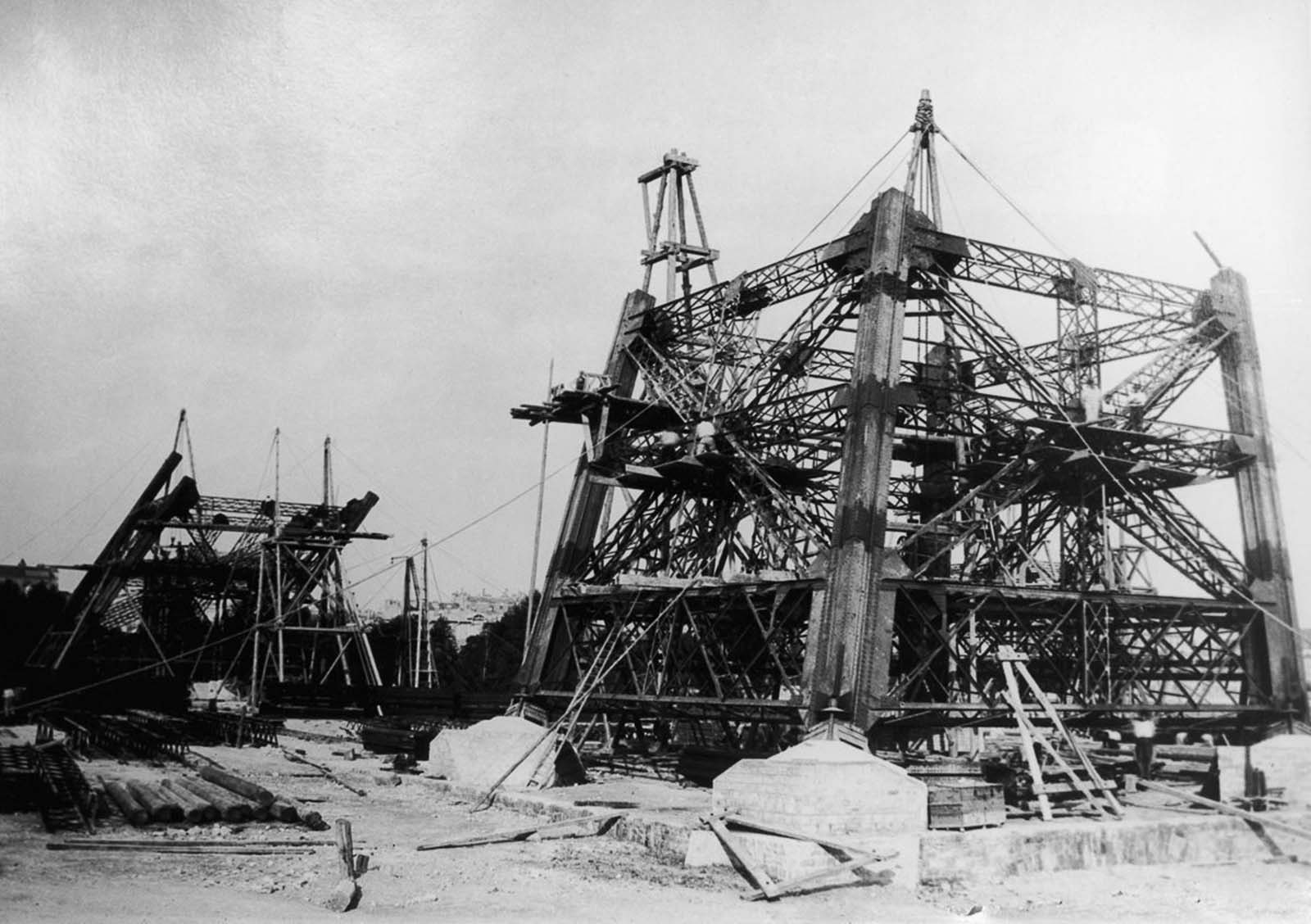

The tower was assembled using wooden scaffolding and small steam cranes mounted onto the tower itself. The assembly of the first level was achieved by the use of twelve temporary wooden scaffolds, 30 meters high, and four larger scaffolds of 40 meters each.

“Sandboxes” and hydraulic jacks – replaced after use by permanent wedges – allowed the metal girders to be positioned to an accuracy of one millimeter. It only took five months to build the foundations and twenty-one to finish assembling the metal pieces of the Tower.

On March 31, 1889, Eiffel celebrated the completion of principal structural work by leading a group of press and officials on a tour of the tower — via the stairs. Upon reaching the top with the hardiest of the party, Eiffel raised a French flag to the booms of a 25-gun salute.

There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts (elevators) and facilities, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the exposition on 6 May; even then, the lifts had not been completed. The tower was an instant success with the public, and nearly 30,000 visitors made the 1,710-step climb to the top before the lifts entered service on 26 May.

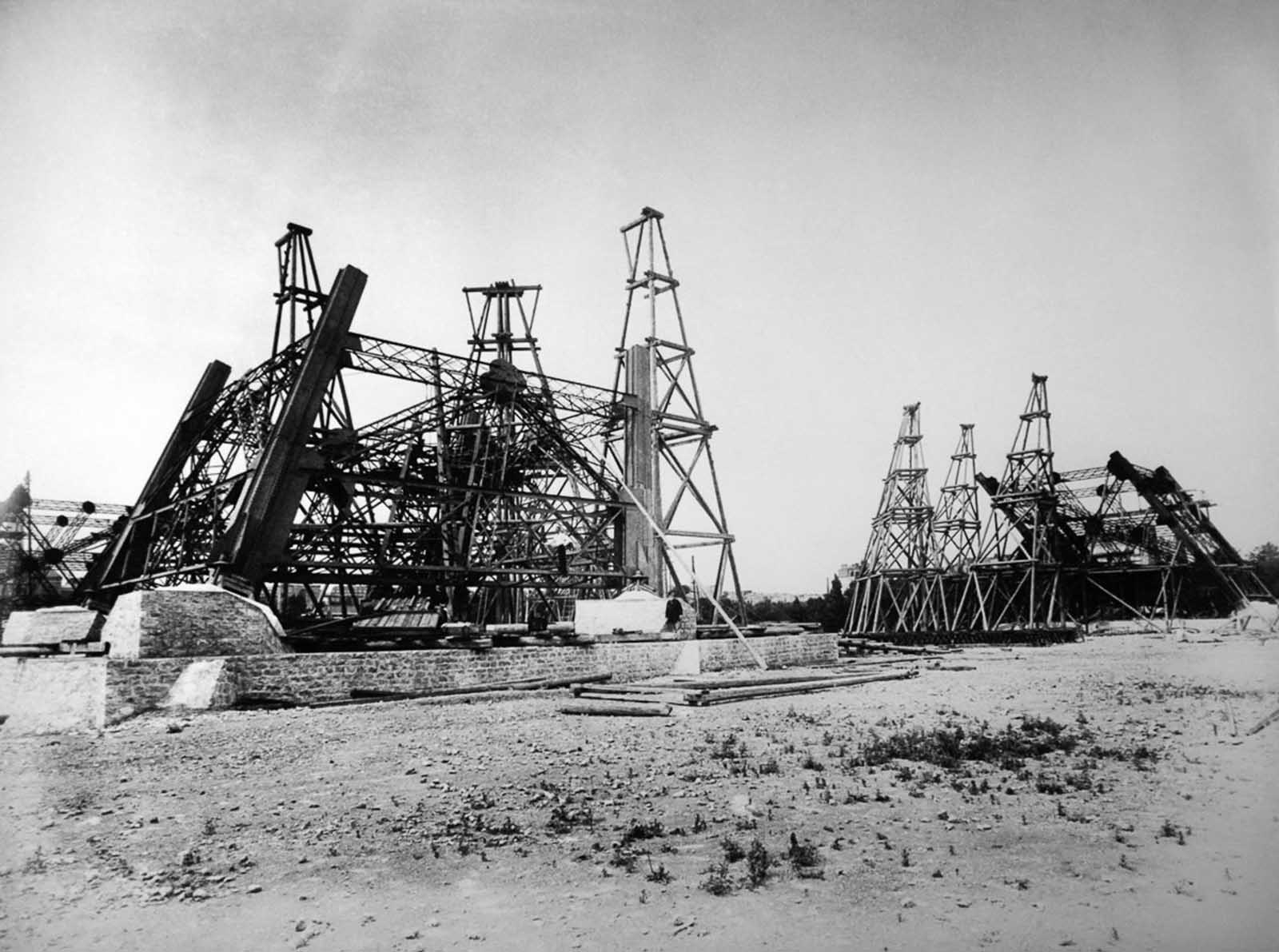

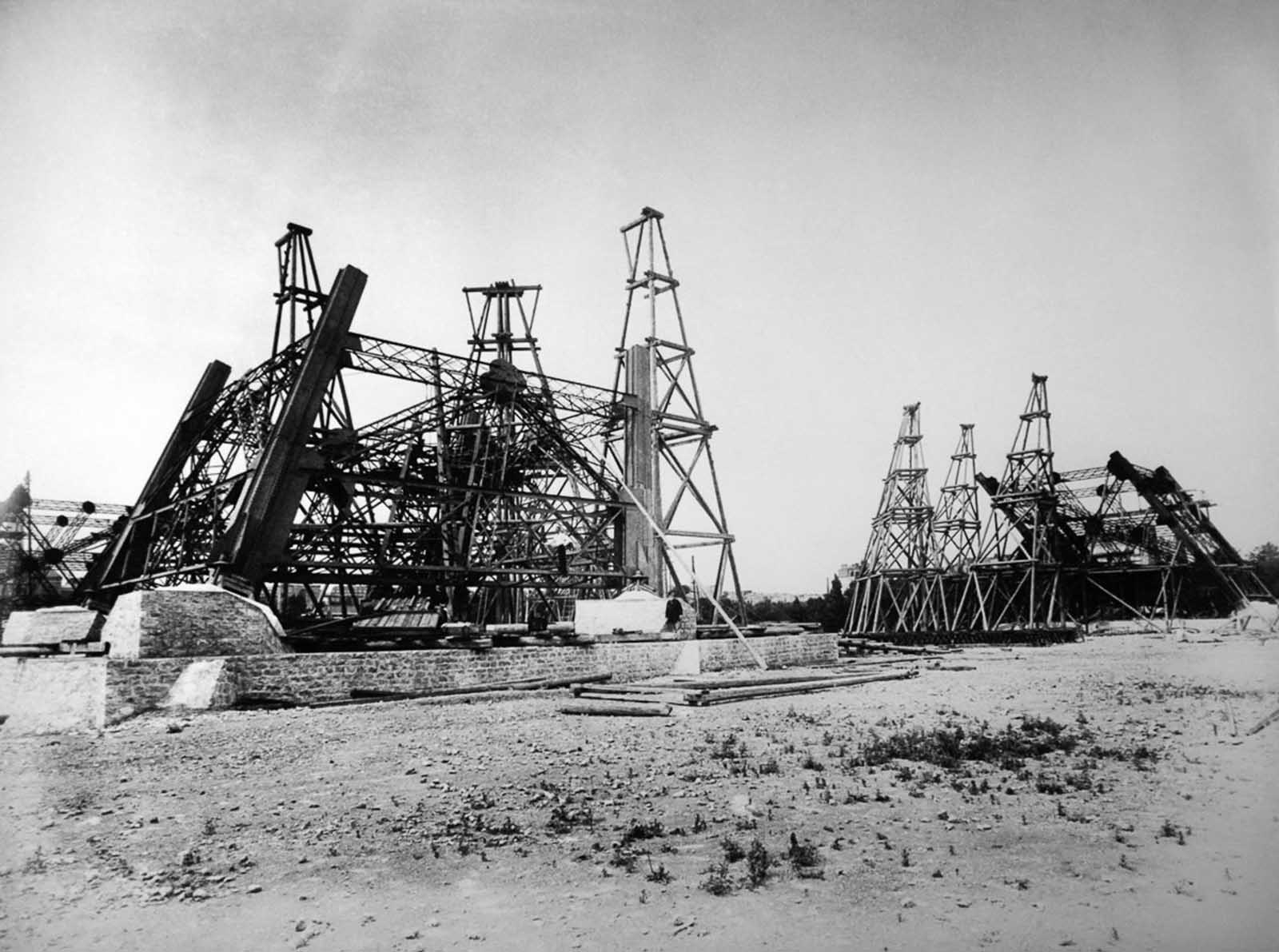

The start of the erection of the metalwork. July 18, 1887.

Each shoe was anchored to the stonework by a pair of bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long.

Millions of visitors during and after the World’s Fair marveled at Paris’ newly erected architectural wonder. Not all of the city’s inhabitants were as enthusiastic, however: Many Parisians either feared it was structurally unsound or considered it an eyesore.

The novelist Guy de Maupassant, for example, allegedly hated the tower so much that he often ate lunch in the restaurant at its base, the only vantage point from which he could completely avoid glimpsing its looming silhouette.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years. It was to be dismantled in 1909 when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris.

The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it should be easy to dismantle) but as the tower proved to be valuable for communication purposes, it was allowed to remain after the expiry of the permit.

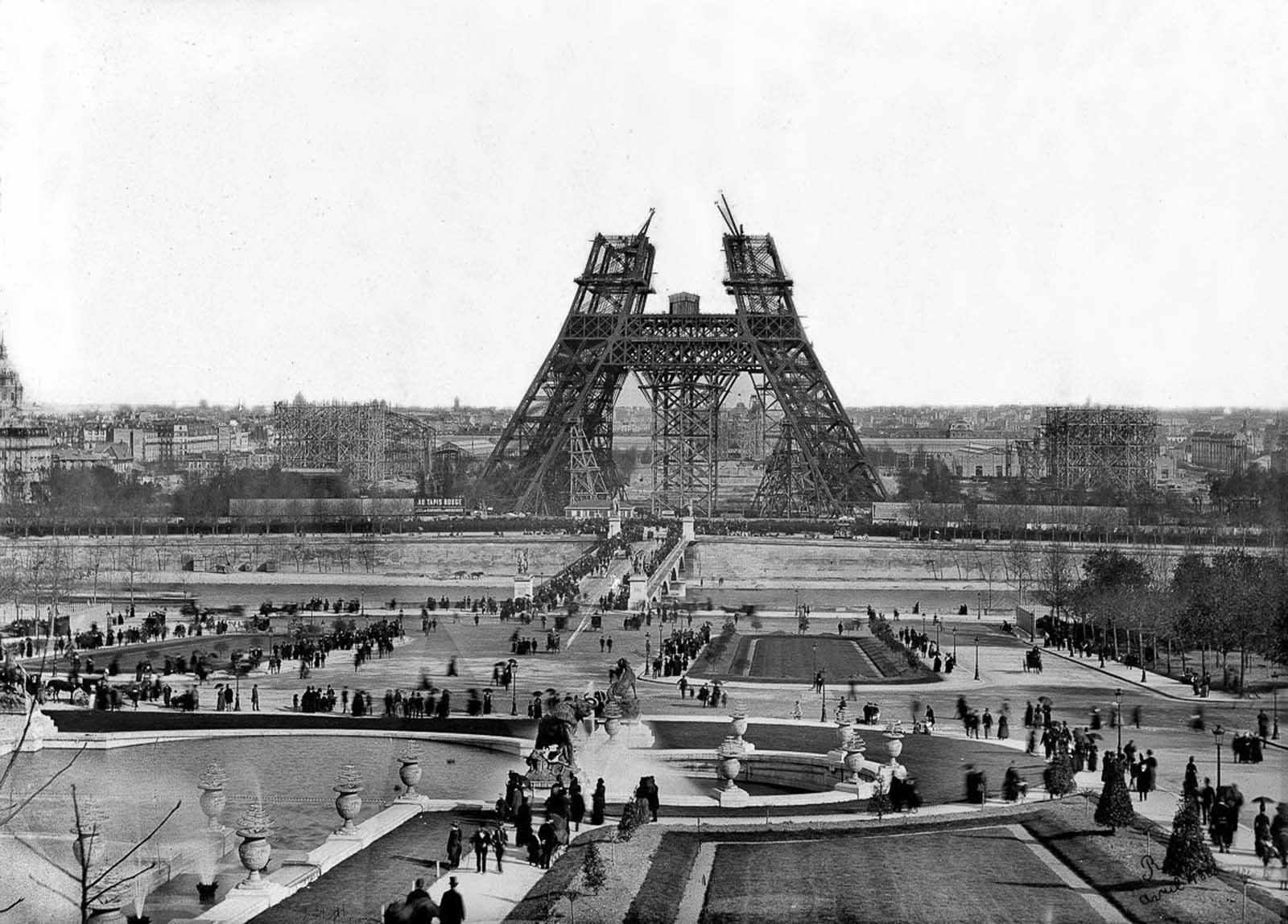

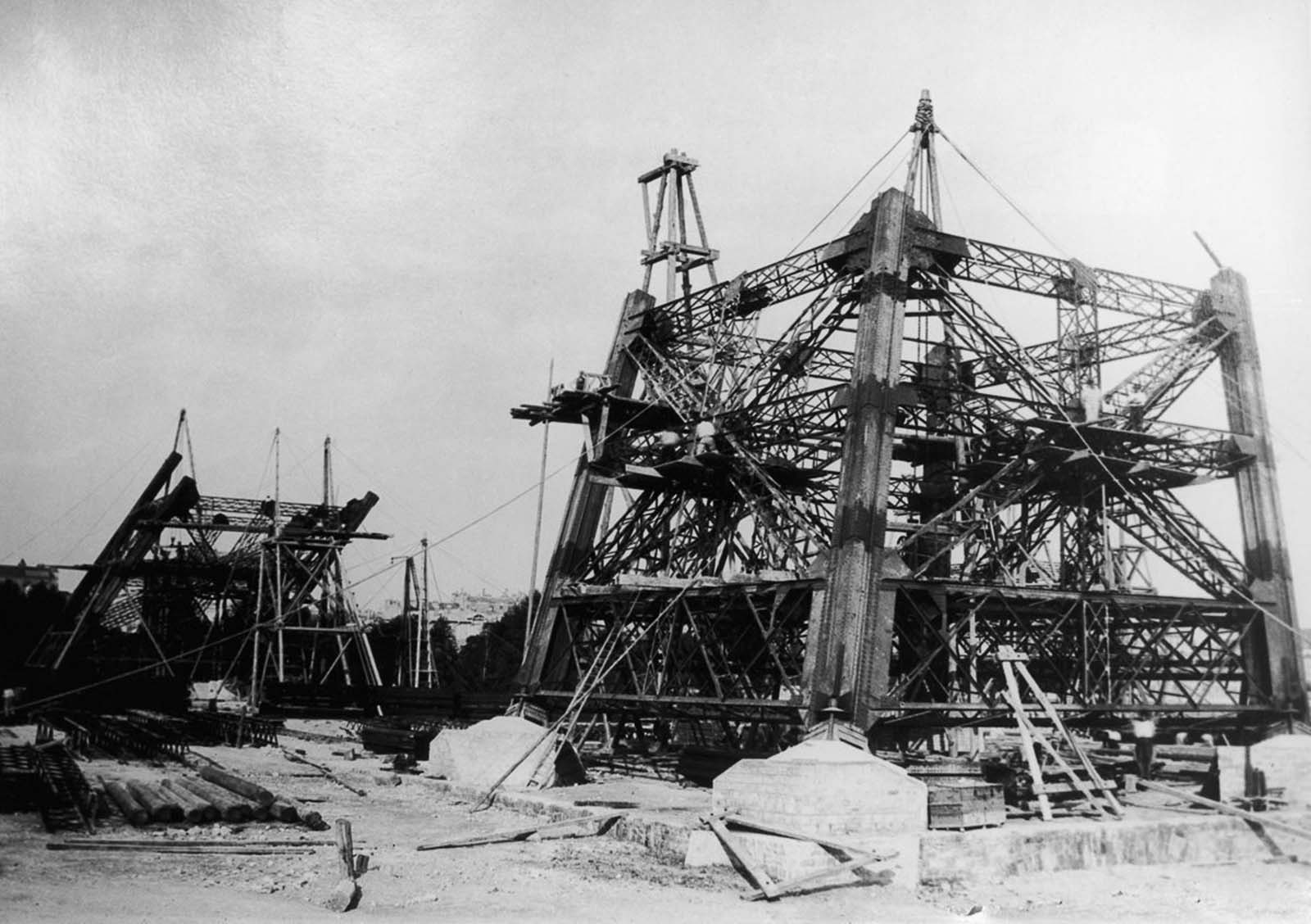

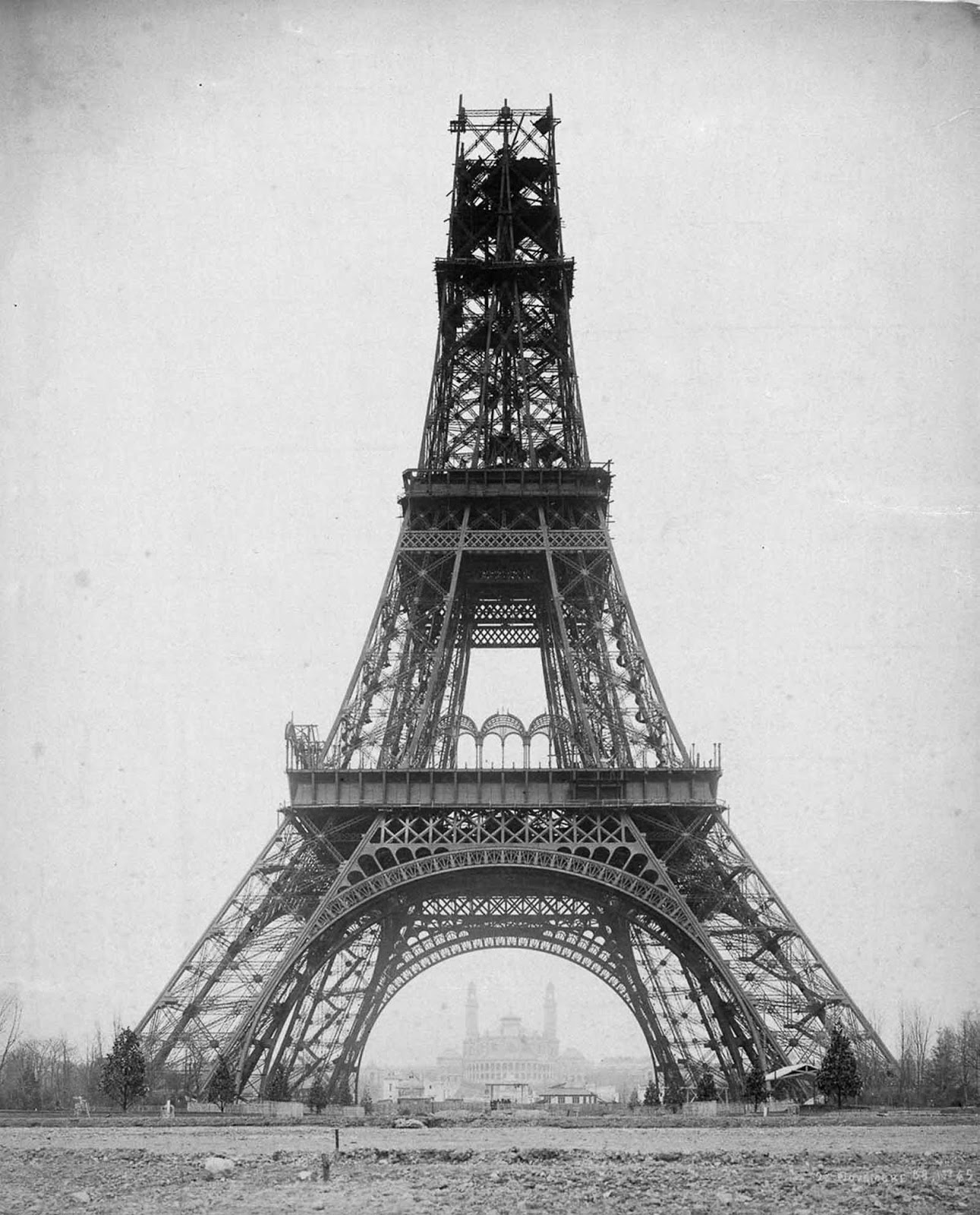

Construction of the legs with scaffolding. 1887.

No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit, it was sent back to the factory for alteration.

In all, 18,038 pieces were joined together using 2.5 million rivets. 1888.

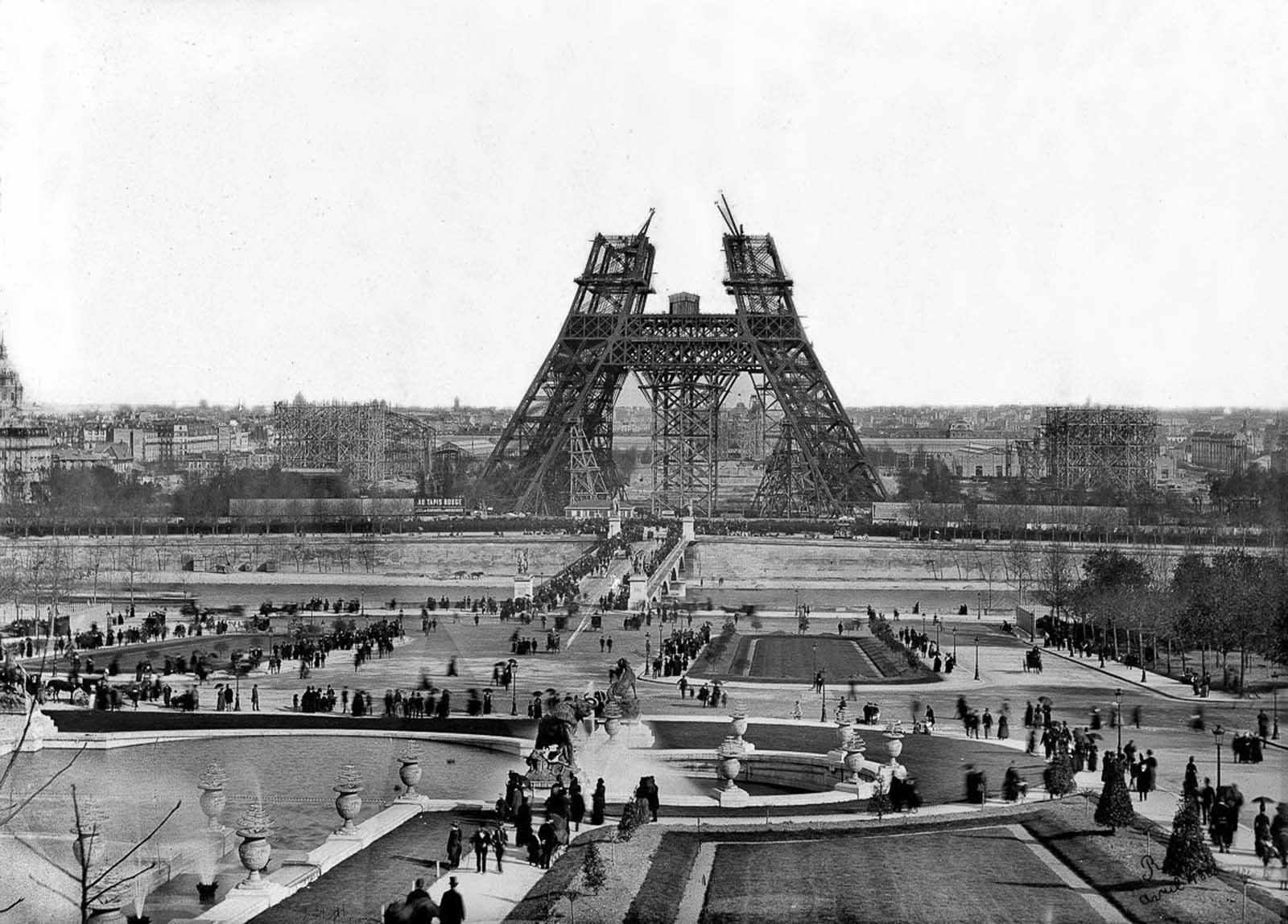

Completion of the first level. March 20, 1888.

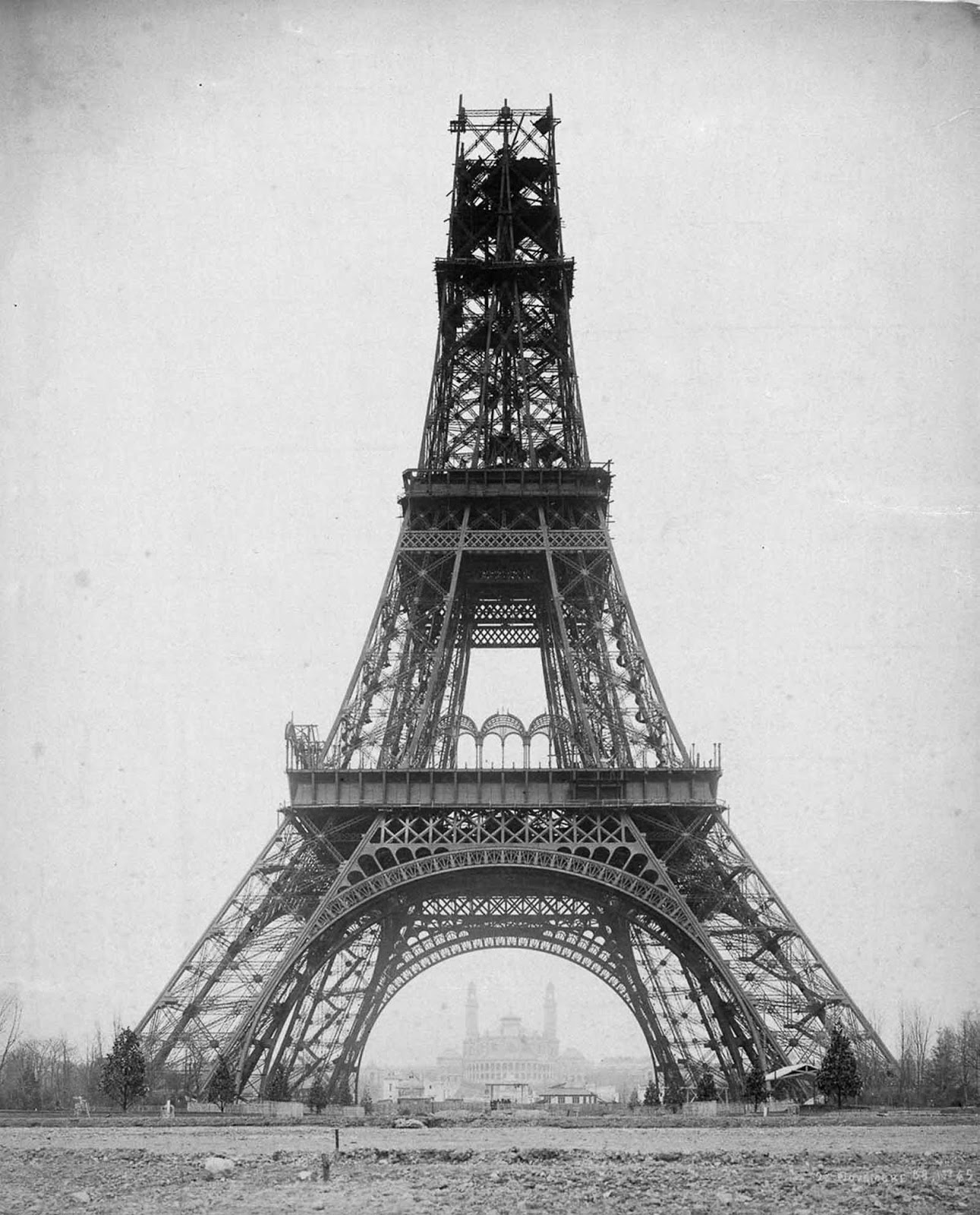

Start of construction on the second stage. May, 1888.

Equipping the tower with adequate and safe passenger lifts was a major concern of the government commission overseeing the Exposition.

The tower on July 1888.

July, 1888.

Construction of the upper stage. December, 1888.

Because of Eiffel’s safety precautions, including the use of movable stagings, guard-rails and screens, only one person died during construction.

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, left, explores the completed tower with a friend.

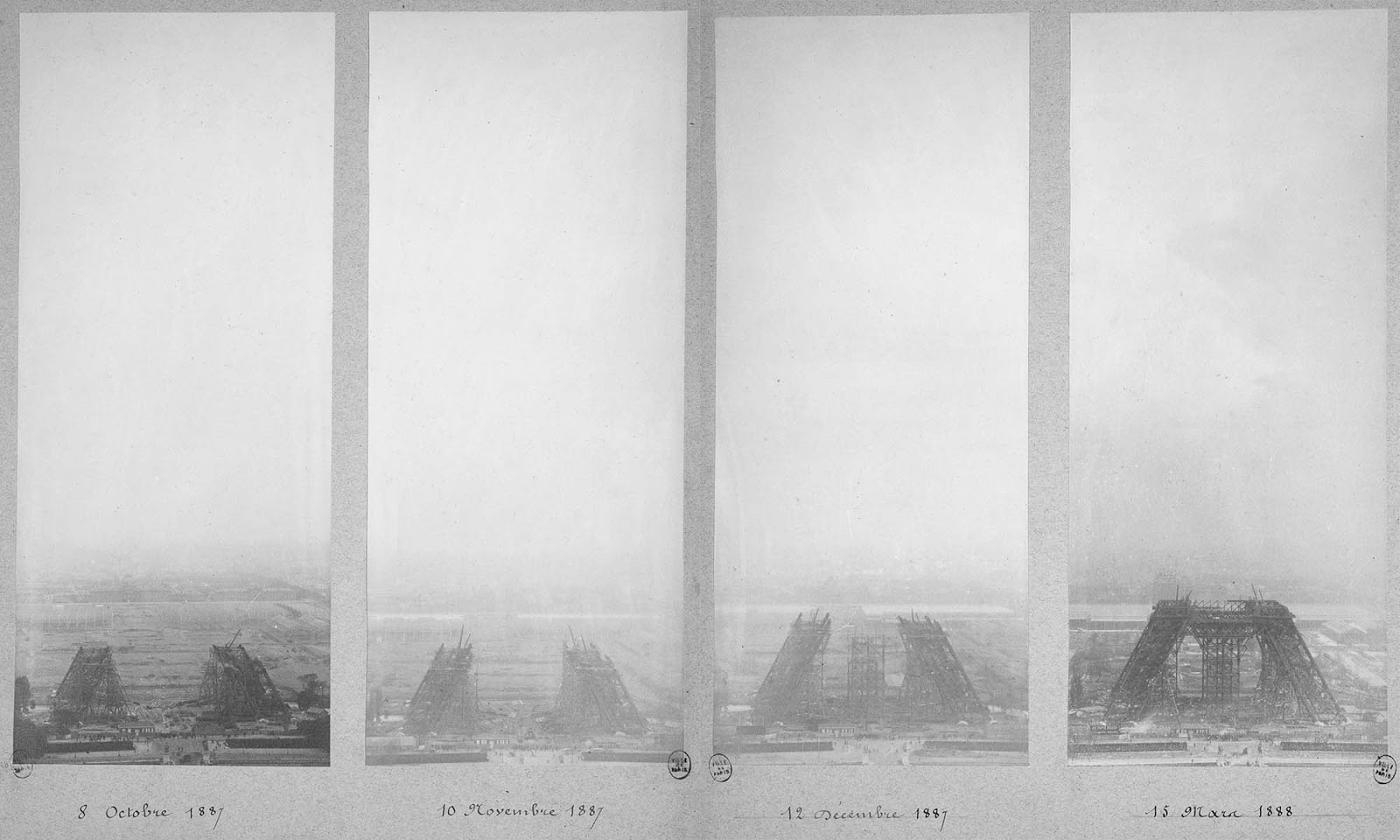

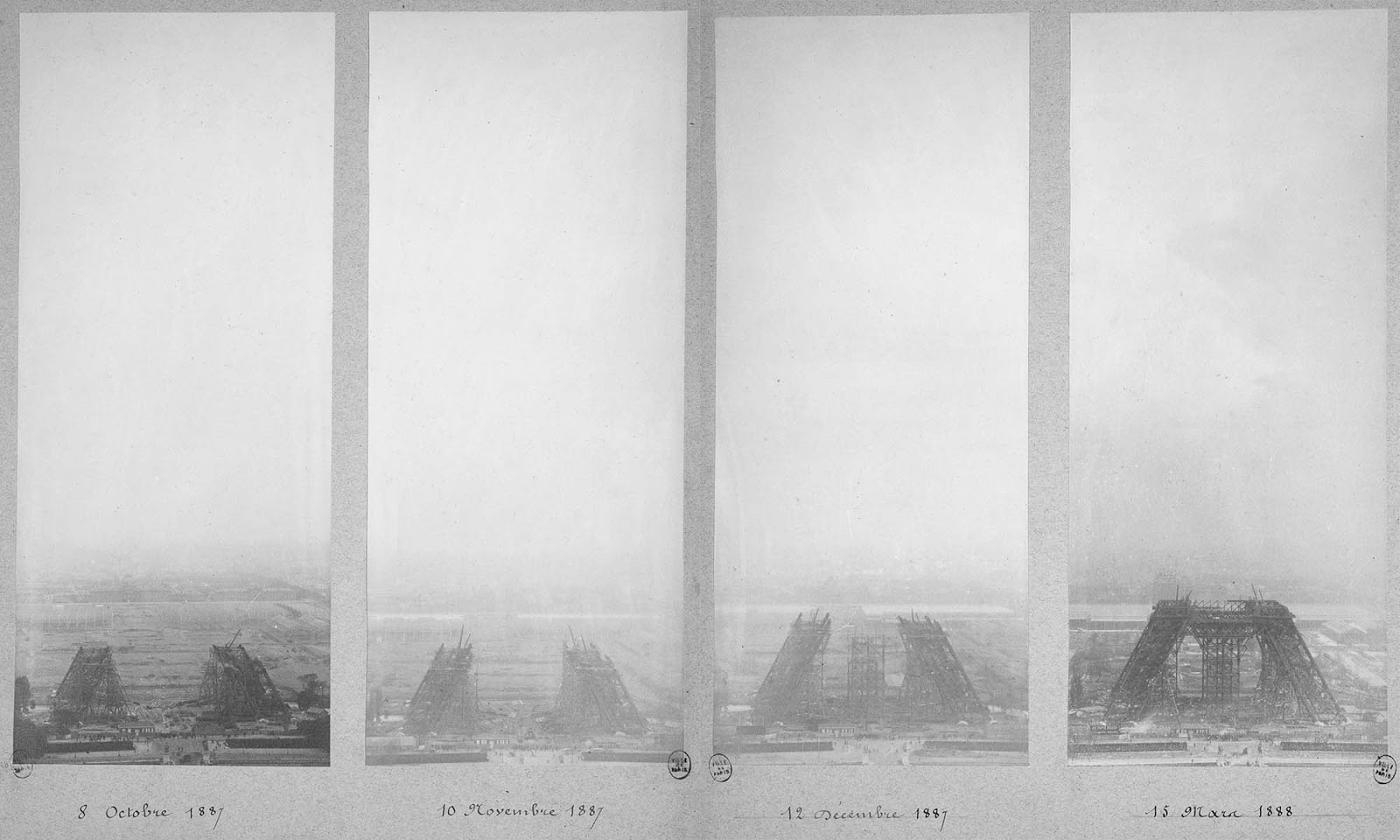

October 1887 – March 1888.

June 1888 – November 1888.

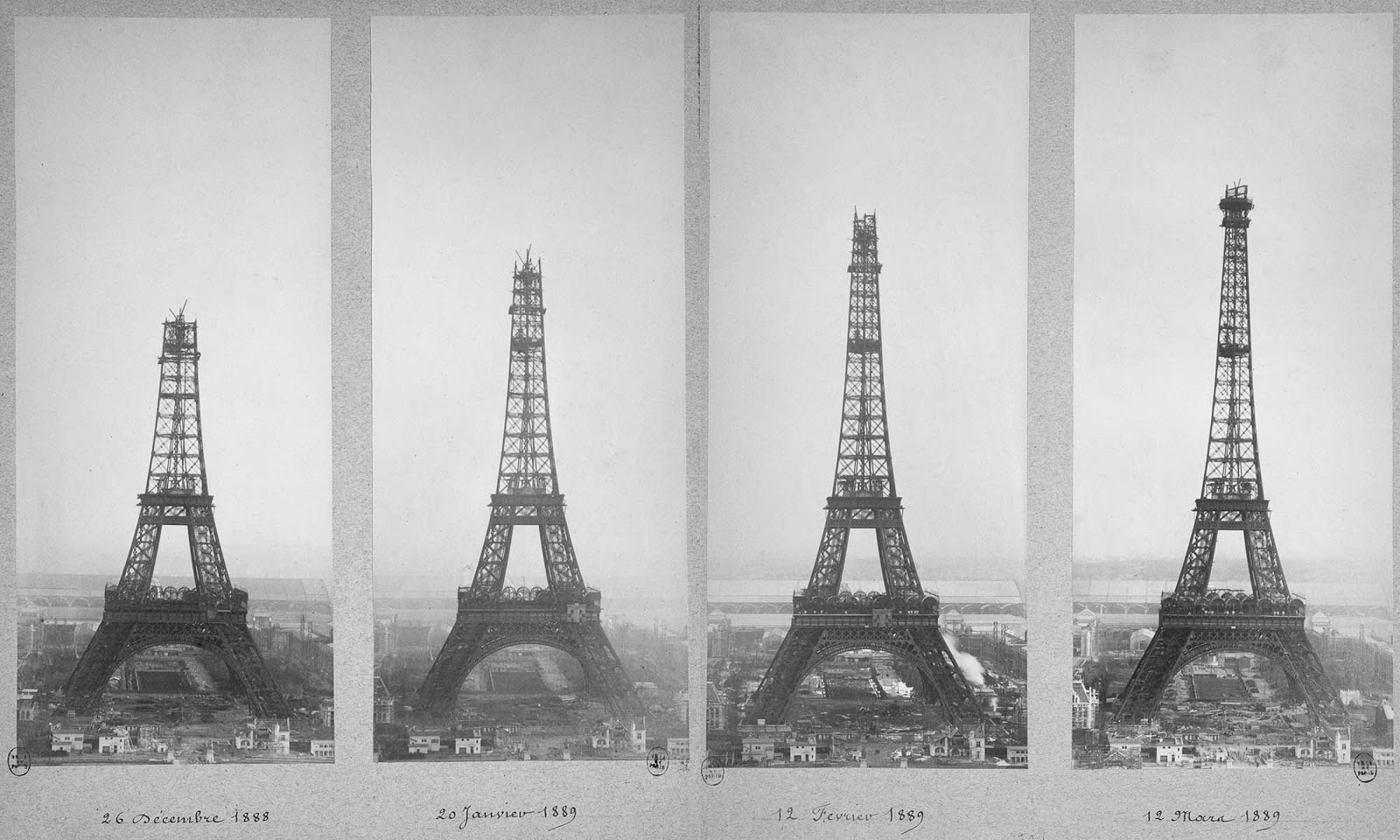

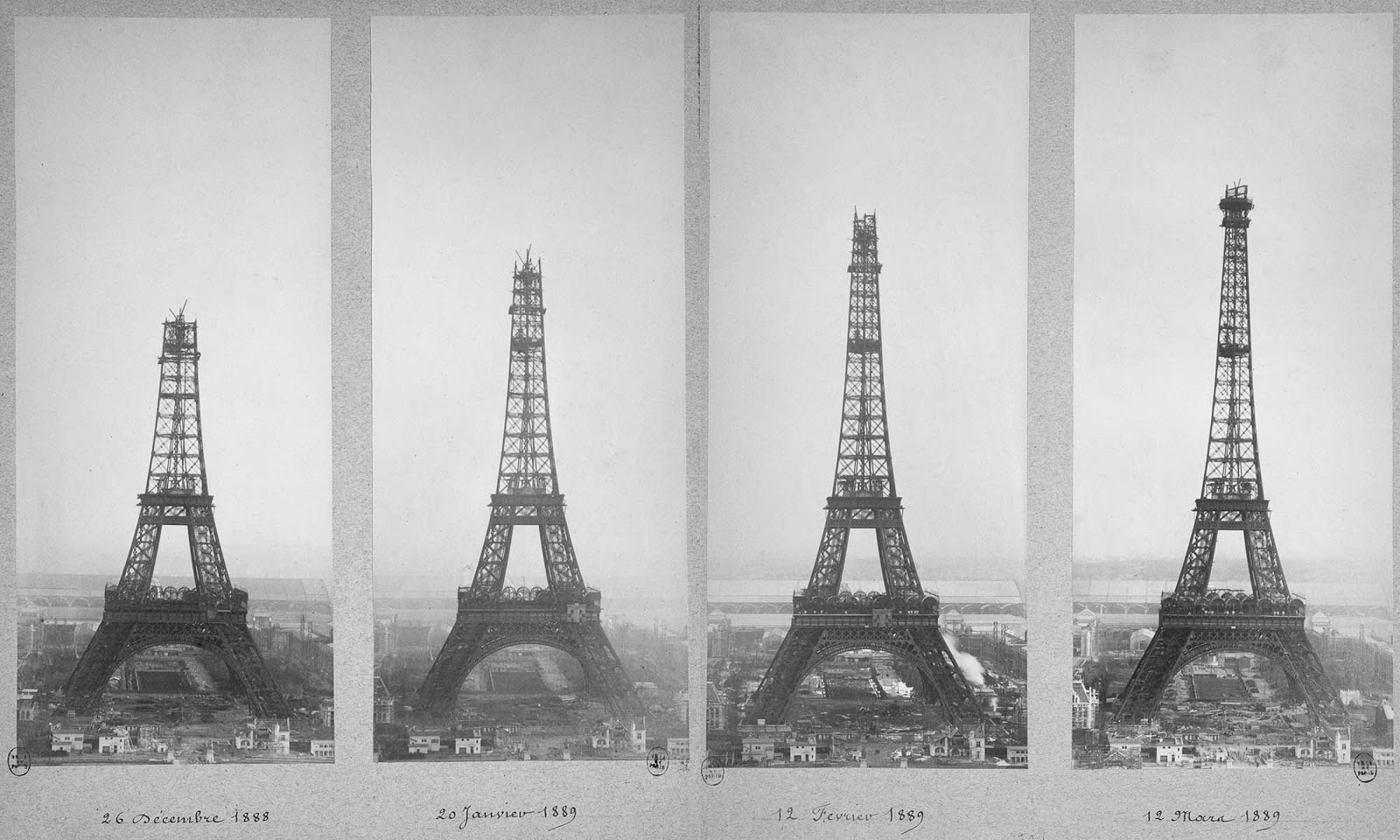

December 1888 – March 1889.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years; it was to be dismantled in 1909, when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris.

After dark, the tower was lit by hundreds of gas lamps, and a beacon sent out three beams of red, white, and blue light. Two searchlights mounted on a circular rail were used to illuminate various buildings of the exposition. 1889.

(Photo credit: National Archives of France / Library of Congress).

Eiffel Tower under construction, 1887-1889

The construction started in January 1887. The proposed tower had been a subject of controversy, drawing criticism from those who did not believe it was feasible and those who objected on artistic grounds.

In 1889, Paris hosted an Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) to mark the 100-year anniversary of the French Revolution. More than 100 artists submitted competing plans for a monument to be built on the Champ-de-Mars, located in central Paris, and serve as the exposition’s entrance.

The commission was granted to Eiffel et Compagnie, a consulting and construction firm owned by the acclaimed bridge builder, architect, and metals expert Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel.

While Eiffel himself often receives full credit for the monument that bears his name, it was one of his employees—a structural engineer named Maurice Koechlin—who came up with and fine-tuned the concept.

The assembly of the supports began on July 1, 1887, and was completed twenty-two months later. All the elements were prepared in Eiffel’s factory located at Levallois-Perret on the outskirts of Paris.

Each of the 18,000 pieces used to construct the Tower were specifically designed and calculated, traced out to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimeter, and then put together forming new pieces around five meters each.

Foundations of the Eiffel Tower.

A team of constructors, who had worked on the great metal viaduct projects, were responsible for the 150 to 300 workers on-site assembling this gigantic erector set.

All the metal pieces of the tower are held together by rivets, a well-refined method of construction at the time the Tower was constructed.

First, the pieces were assembled in the factory using bolts, later to be replaced one by one with thermally assembled rivets, which contracted during cooling thus ensuring a very tight fit.

A team of four men was needed for each rivet assembled: one to heat it up, another to hold it in place, a third to shape the head and a fourth to beat it with a sledgehammer. Only a third of the 2,500,000 rivets used in the construction of the Tower were inserted directly on site.

One of the stone and cement foundations for the tower’s legs. April, 1887.

Workers prepare the foundation of the Eiffel Tower on April 25, 1887.

The uprights rest on concrete foundations installed a few meters below ground-level on top of a layer of compacted gravel. Each corner edge rests on its own supporting block, applying to it a pressure of 3 to 4 kilograms per square centimeter, and each block is joined to the others by walls.

On the Seine side of the construction, the builders used watertight metal caissons and injected compressed air, so that they were able to work below the level of the water.

The tower was assembled using wooden scaffolding and small steam cranes mounted onto the tower itself. The assembly of the first level was achieved by the use of twelve temporary wooden scaffolds, 30 meters high, and four larger scaffolds of 40 meters each.

“Sandboxes” and hydraulic jacks – replaced after use by permanent wedges – allowed the metal girders to be positioned to an accuracy of one millimeter. It only took five months to build the foundations and twenty-one to finish assembling the metal pieces of the Tower.

On March 31, 1889, Eiffel celebrated the completion of principal structural work by leading a group of press and officials on a tour of the tower — via the stairs. Upon reaching the top with the hardiest of the party, Eiffel raised a French flag to the booms of a 25-gun salute.

There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts (elevators) and facilities, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the exposition on 6 May; even then, the lifts had not been completed. The tower was an instant success with the public, and nearly 30,000 visitors made the 1,710-step climb to the top before the lifts entered service on 26 May.

The start of the erection of the metalwork. July 18, 1887.

Each shoe was anchored to the stonework by a pair of bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long.

Millions of visitors during and after the World’s Fair marveled at Paris’ newly erected architectural wonder. Not all of the city’s inhabitants were as enthusiastic, however: Many Parisians either feared it was structurally unsound or considered it an eyesore.

The novelist Guy de Maupassant, for example, allegedly hated the tower so much that he often ate lunch in the restaurant at its base, the only vantage point from which he could completely avoid glimpsing its looming silhouette.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years. It was to be dismantled in 1909 when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris.

The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it should be easy to dismantle) but as the tower proved to be valuable for communication purposes, it was allowed to remain after the expiry of the permit.

Construction of the legs with scaffolding. 1887.

No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit, it was sent back to the factory for alteration.

In all, 18,038 pieces were joined together using 2.5 million rivets. 1888.

Completion of the first level. March 20, 1888.

Start of construction on the second stage. May, 1888.

Equipping the tower with adequate and safe passenger lifts was a major concern of the government commission overseeing the Exposition.

The tower on July 1888.

July, 1888.

Construction of the upper stage. December, 1888.

Because of Eiffel’s safety precautions, including the use of movable stagings, guard-rails and screens, only one person died during construction.

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, left, explores the completed tower with a friend.

October 1887 – March 1888.

June 1888 – November 1888.

December 1888 – March 1889.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years; it was to be dismantled in 1909, when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris.

After dark, the tower was lit by hundreds of gas lamps, and a beacon sent out three beams of red, white, and blue light. Two searchlights mounted on a circular rail were used to illuminate various buildings of the exposition. 1889.

(Photo credit: National Archives of France / Library of Congress).