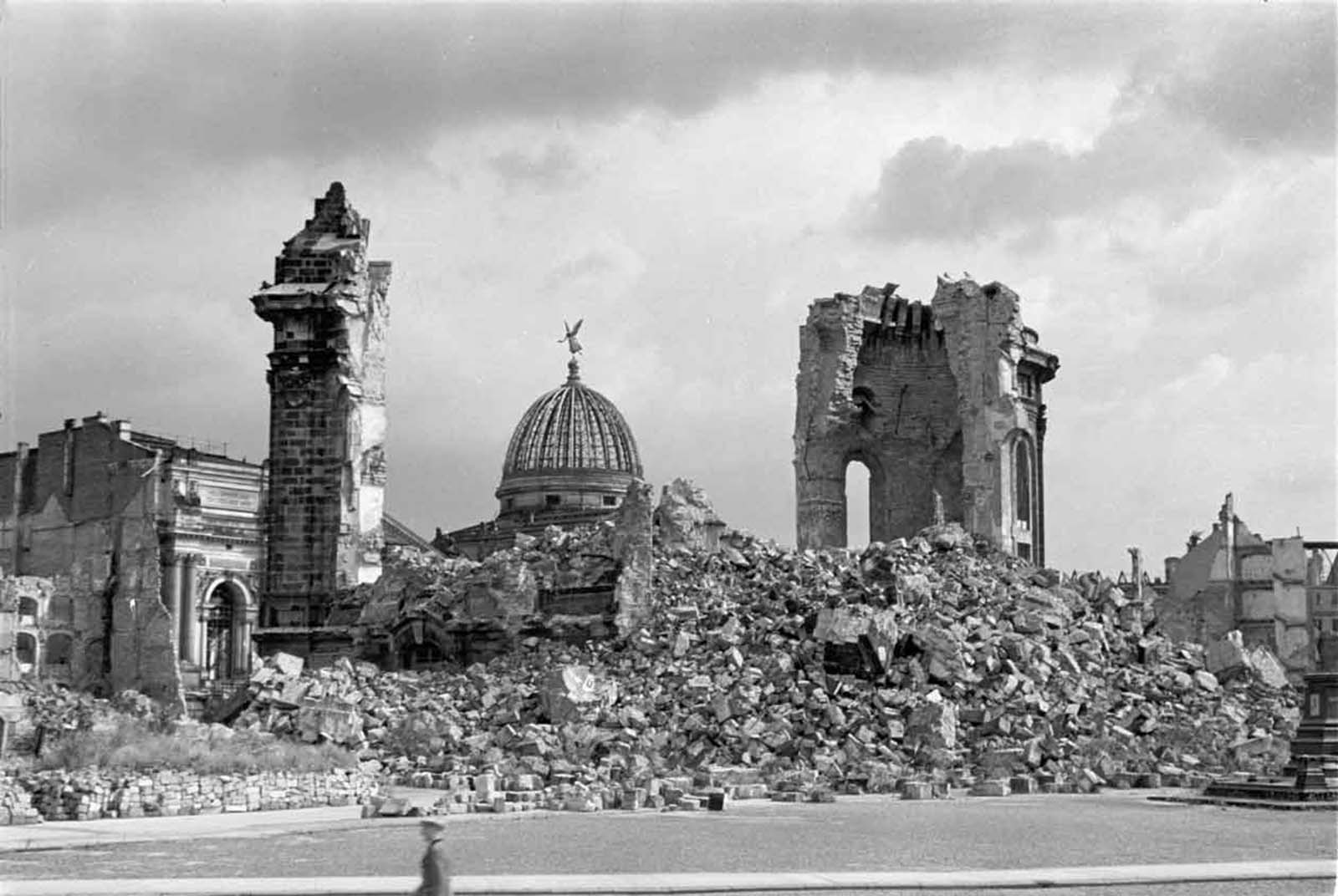

Dresden in ruins after Allied bombings, February 1945.

At the end of World War II, the city of Dresden was in ruins, all its buildings destroyed and thousands of civilians dead.

The scale of the death and destruction, coming so late in the war, along with significant questions about the legitimacy of the targets destroyed have led to years of debate about whether the attack was justified, or whether it should be labeled a war crime. The bombing of Dresden has become one of the most controversial decisions made in the European theater.

Before World War II, Dresden was called “the Florence of the Elbe” and was regarded as one the world’s most beautiful cities for its architecture and museums, it had numerous beautiful baroque and rococo-style buildings, palaces, and cathedrals.

Beginning on the night of February 13, 1945, more than 1,200 heavy bombers dropped nearly 4,000 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city in four successive raids.

Although no German city remained isolated from Hitler’s war machine, Dresden’s contribution to the war effort was minimal compared with other German cities.

As Hitler had thrown much of his surviving forces into a defense of Berlin in the north, city defenses were minimal, and the Russians would have had little trouble capturing Dresden. It seemed an unlikely target for a major Allied air attack.

An important aspect of the Allied air war against Germany involved what is known as “area” or “saturation” bombing.

In this British Official Photo, on the night of February 13 and the morning of February 14, 1945, Lancasters of R.A.F. Bomber Command made two very heavy attacks on Dresden, Germany. Heavy bombers of the U.S. 8th Air Force attacked this target the following day. The smoke from fires still burning drifted across Dresden on February 14, 1945.

In area bombing, all enemy industry–not just war munitions–is targeted, and civilian portions of cities are obliterated along with troop areas.

Before the advent of the atomic bomb, cities were most effectively destroyed through the use of incendiary bombs that caused unnaturally fierce fires in enemy cities.

Such attacks, Allied command reasoned, would ravage the German economy, break the morale of the German people and force an early surrender.

The demolished city of Dresden.

On the night of February 13, 1945, hundreds of RAF bombers descended on Dresden in two waves, dropping their lethal cargo indiscriminately over the city.

The city’s air defenses were so weak that only six Lancaster bombers were shot down.

By the morning, some 800 British bombers had dropped more than 1,400 tons of high-explosive bombs and more than 1,100 tons of incendiaries on Dresden, creating a great firestorm that destroyed most of the city and killed numerous civilians.

Later that day, as survivors made their way out of the smoldering city, more than 300 U.S. bombers began bombing Dresden’s railways, bridges, and transportation facilities, killing thousands more.

Over ninety percent of the city center was destroyed.

On February 15, another 200 U.S. bombers continued their assault on the city’s infrastructure.

All told, the bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force dropped more than 950 tons of high-explosive bombs and more than 290 tons of incendiaries on Dresden.

Later, the Eighth Air Force would drop 2,800 more tons of bombs on Dresden in three other attacks before the war’s end.

After the war, investigators from various countries, and with varying political motives, calculated the number of civilians killed to be as little as 8,000 to more than 200,000. Estimates today range from 35,000 to 135,000.

The destruction of the city provoked unease in intellectual circles in Britain. According to Max Hastings, by February 1945, attacks upon German cities had become largely irrelevant to the outcome of the war and the name of Dresden resonated with cultured people all over Europe.

Looking at photographs of Dresden after the attack, in which the few buildings still standing are completely gutted, it seems improbable that only 35,000 of the million or so people in Dresden at the time were killed.

At the end of the war, Dresden was so badly damaged that the city was basically leveled.

A handful of historic buildings–the Zwinger Palace, the Dresden State Opera House, and several fine churches–were carefully reconstructed out of the rubble, but the rest of the city was rebuilt with plain modern buildings.

American author Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), who was a prisoner of war in Dresden during the Allied attack and tackled the controversial event in his book “Slaughterhouse-Five,” said of postwar Dresden: “It looked a lot like Dayton, Ohio, more open spaces than Dayton has. There must be tons of human bone meal in the ground”.

A general view of the panorama display depicting the city of Dresden in the aftermath of the 1945 Allied firebombing.

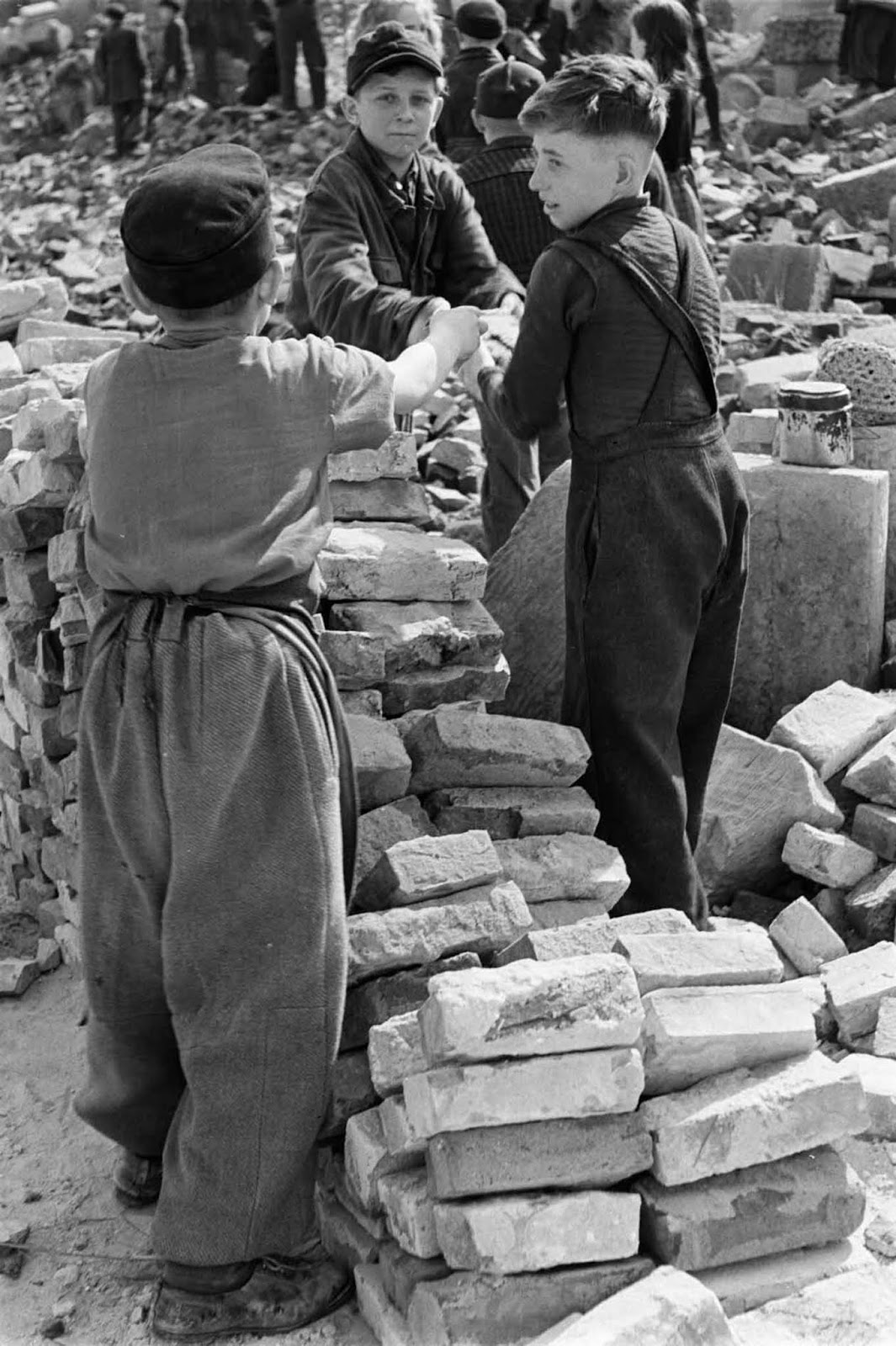

Children cleaning up the ruined city.

Theodor Rosenhauer in the midst of ruins in Dresden working on his oil painting “View of the Japanese Palace after the Bombing”.

Women cleaning up the destroyed city.

The destruction was appalling.

The attack had been prompted by Dresden’s position as a significant hub for both transport and industry.

More than half of that bombing’s mass were explosives, wrecking Dresden’s buildings.

The explosive force created a firestorm, at a temperature above 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Even at the time, the attack was questioned by Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Great Britain at the time. As he put it, “The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing.”

Of 28,410 houses in central Dresden, 24,866 were destroyed. 15 sq km totally demolished—of which there were: 14,000 homes, 72 schools, 22 hospitals, 19 churches, 5 theaters, 50 banks, 31 dept stores, 31 hotels, 62 administrative buildings.

(Photo credit: Deutsche Fotothek / Picture Alliance / US Army Archives).