A pre-war photograph of Hiroshima’s vibrant downtown shopping district near the center of town, facing east. Only rubble and a few utility poles remained after the nuclear explosion and resultant fires.

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of both industrial and military significance. A number of military units were located nearby, the most important of which was the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata’s Second General Army, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan, and was located in Hiroshima Castle. Hata’s command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly anticipated.

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military, but it also had large stockpiles of military supplies. The city was also a communications center, a key port for shipping, and an assembly area for troops.

It was a beehive of war industry, manufacturing parts for planes and boats, for bombs, rifles, and handguns; children were shown how to construct and hurl gasoline bombs and the wheelchair-bound and bedridden were assembling booby traps to be planted in the beaches of Kyushu.

A new slogan appeared on the walls of Hiroshima: “FORGET SELF! ALL OUT FOR YOUR COUNTRY!”. It was also the second-largest city in Japan after Kyoto that was still undamaged by air raids.

Looking upstream on the Motoyasugawa, toward the Product Exhibition Hall building (dome) in Hiroshima, before the bombing. The domed building was almost directly below the detonation, which occurred in mid-air, about 2,000 feet (600 meters) above this spot. Today, much of the building remains standing and is known as the Atomic Bomb Dome, or the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small timber-made workshops set among Japanese houses.

A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of timber with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around timber frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war but prior to the atomic bombing, the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack, the population was approximately 340,000–350,000.

Looking northeast along Teramachi, the Street of Temples, in pre-war Hiroshima. This district was completely ruined.

Residents wondered why Hiroshima had been spared destruction by firebombing. Some speculated that the city was to be saved for U.S. occupation headquarters, others thought perhaps their relatives in Hawaii and California had petitioned the U.S. government to avoid bombing Hiroshima.

More realistic city officials had ordered buildings torn down to create long, straight firebreaks, beginning in 1944. Firebreaks continued to be expanded and extended up to the morning of August 6, 1945.

On August 6, the U.S. dropped a uranium gun-type (Little Boy) bomb on Hiroshima, and American President Harry S. Truman called for Japan’s surrender, warning it to “expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth”.

On Monday, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m., the nuclear weapon “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima by an American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, flown by Colonel Paul Tibbets, directly killing an estimated 70,000 people, including 20,000 Japanese combatants and 2,000 Korean slave laborers.

By the end of the year, injury and radiation brought the total number of deaths to 90,000–166,000. The population before the bombing was around 340,000 to 350,000. About 70% of the city’s buildings were destroyed, and another 7% severely damaged.

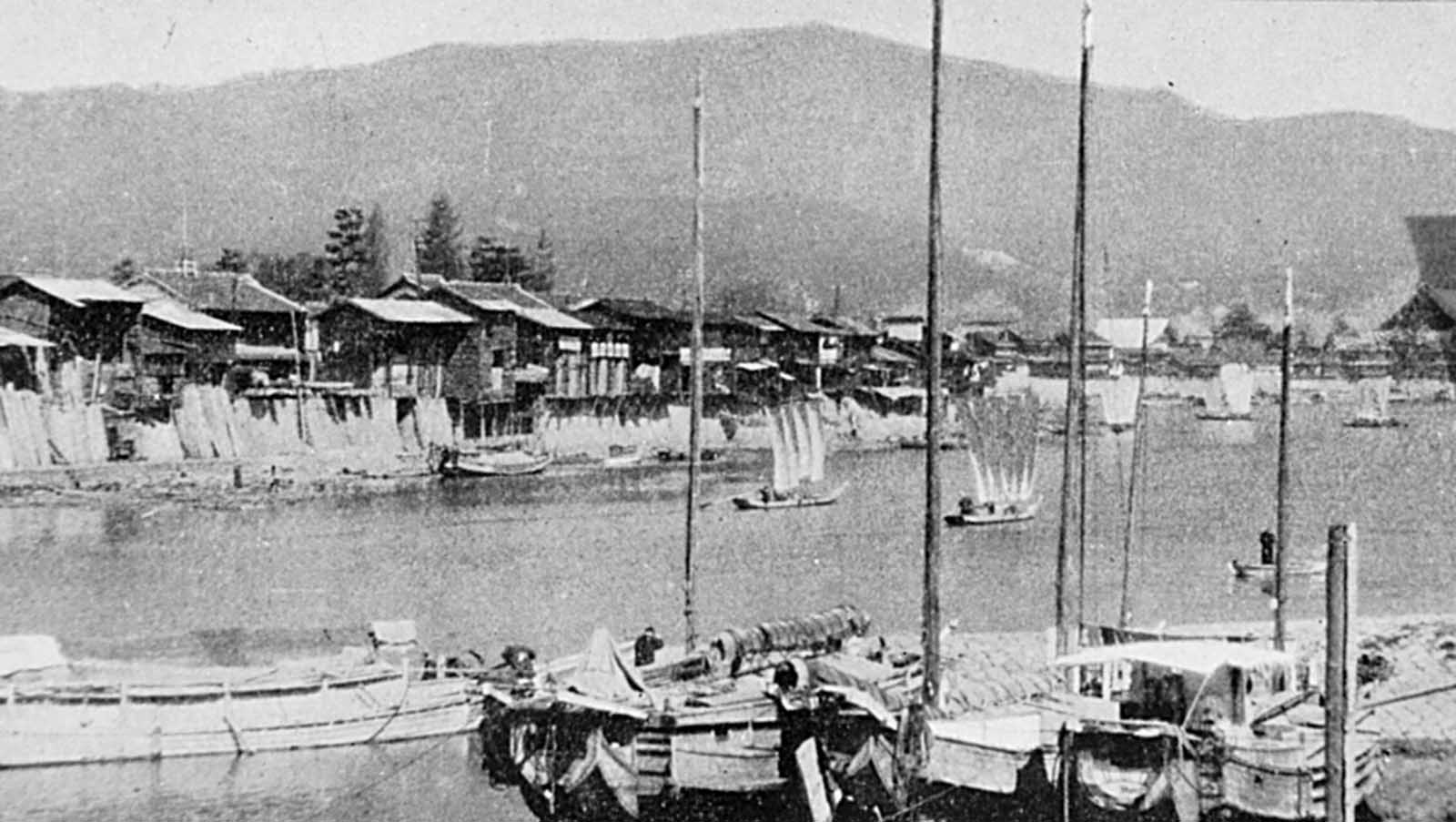

Looking north from the vicinity of the Aioi Bridge (the central T-shaped bridge targeted by the bomb). Wooden houses line the bank of the Otagawa, with traditional Japanese riverboats in the foreground.

Aerial view of the densely built-up area of Hiroshima along the Motoyasugawa, looking upstream. Except for the very heavy masonry structures, the entire area was devastated. Ground zero of the atomic bomb was upper right in the photo.

Hiroshima Station, between 1912 and 1945.

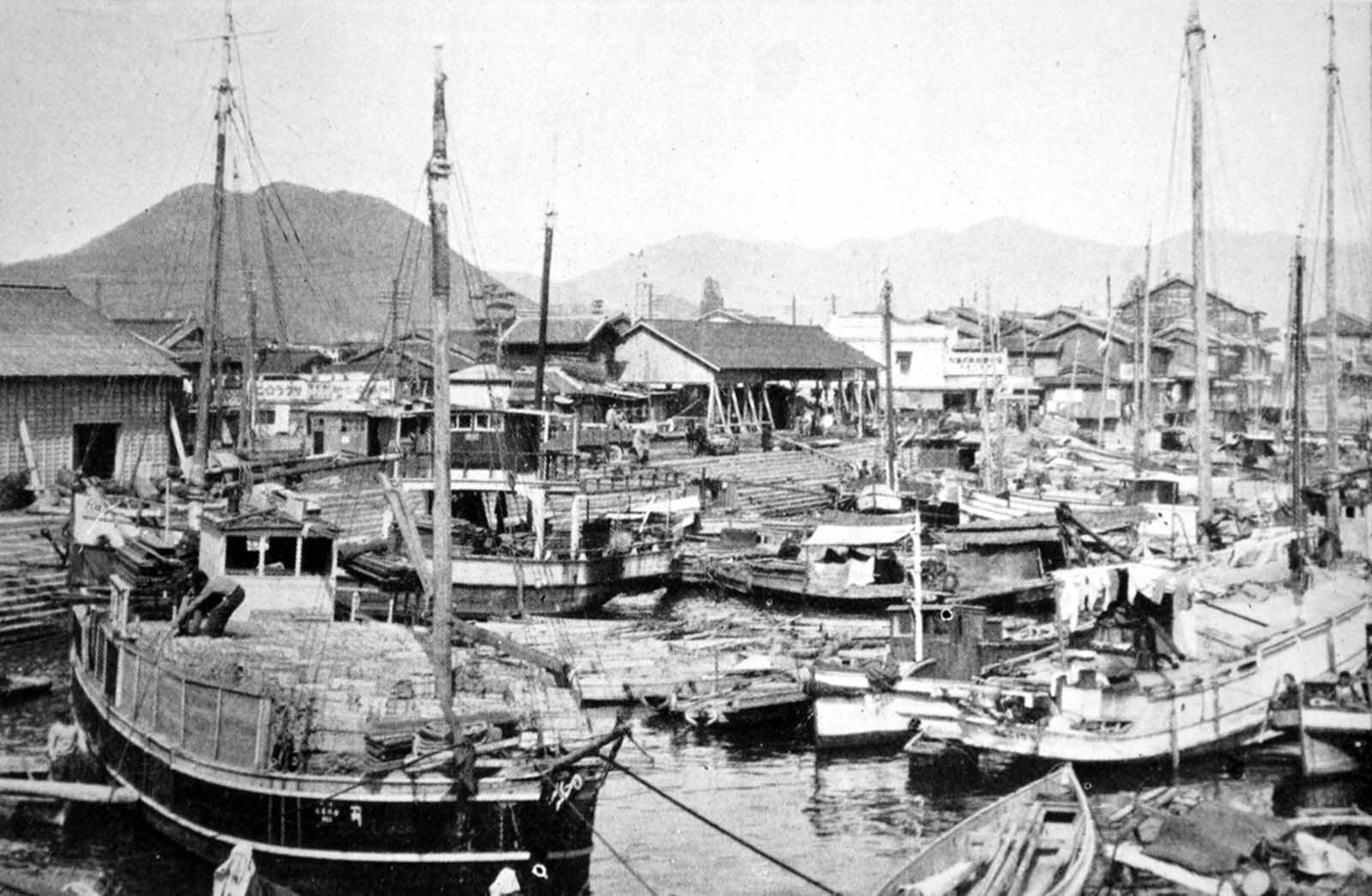

A pre-war photo of Ujina Harbor. This relatively small harbor was developed as the port for Hiroshima and was one of the principal embarkation depots for the Japanese Army during World War II.

On August 6, 1945, a mushroom cloud billows into the sky about one hour after an atomic bomb was dropped by American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, detonating above Hiroshima, Japan. Nearly 80,000 people are believed to have been killed immediately, with possibly another 60,000 survivors dying of injuries and radiation exposure by 1950.

Survivors of the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare await emergency medical treatment in Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945.

Shortly after the atomic bomb was dropped over the Japanese city of Hiroshima, survivors receive emergency treatment from military medics on August 6, 1945.

Civilians gather in front of the ruined Hiroshima Station, months after the bombing.

Japanese troops rest in the Hiroshima railway station after the atomic bomb explosion.

Streetcars, bicyclists, and pedestrians make their way through the wreckage of Hiroshima.

One of several Japanese fire engines transferred to Hiroshima shortly after the bombing.

Hiroshima after the bombing.

A Japanese woman and her child, casualties in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, lie on a blanket on the floor of a damaged bank building converted into a hospital and located near the center of the devastated town, on October 6, 1945.

The devastated landscape of Hiroshima, months after the bombing.

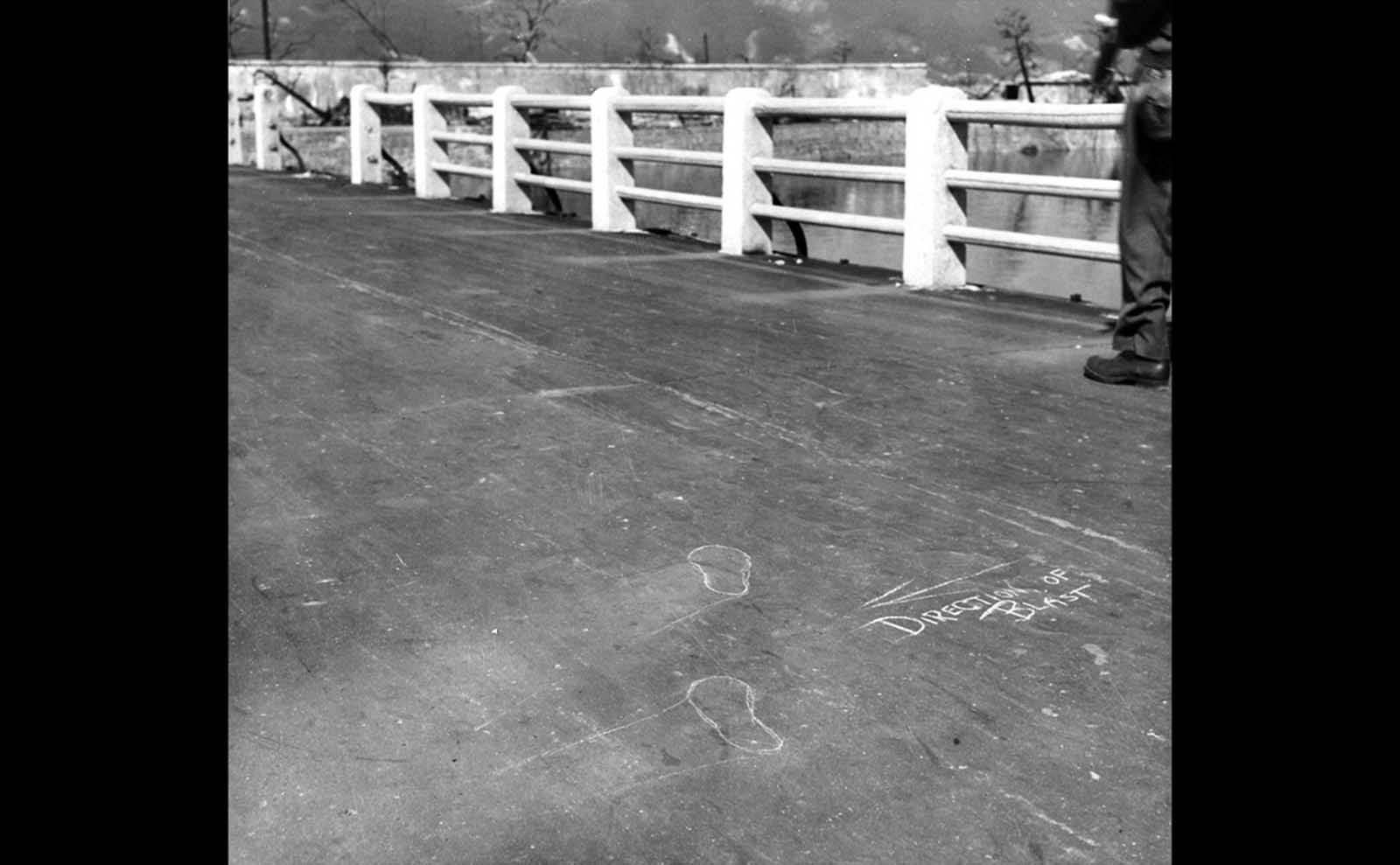

“Direction of blast” chalk marks and outlines of the feet of a victim caught in the explosion. The intense heat of the initial flash of the detonation seared every nearby surface, leaving inverted “shadows,” like those seen on this bridge left by the railings and by a person who had been standing in this place.

Post office savings bank, Hiroshima. Shadow of window frame left on fiberboard walls made by the flash of the detonation. October 4, 1945.

In Hiroshima, gas tanks showing shadowing effects of the flash on asphalt paint.

Two Japanese men sit in a makeshift office set up in a ruined building in Hiroshima.

The shattered Nagarekawa Methodist Church stands amid the ruins of Hiroshima.

A huge expanse of ruins left after the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

An aerial view of Hiroshima, some time after the atom bomb was dropped on this Japanese city. Compare this with pre-war photo number 5 above.

A Japanese soldier walks through a completely leveled area of Hiroshima in September 1945.

The radiation from the explosion created permanent shadows As thermal radiation travels in straight lines from the fireball, any opaque object in its path produces a ‘nuclear shadow’.

Hence the radiation produced permanent nuclear shadows of objects and even people around the sites which can be seen even today. The heat of the explosion instantly vaporized the bodies of people in the near vicinity but left their shadows.

About 12 cyanide pills were kept in the cockpit of the Enola Gay (plane carrying A-bomb). The pilots were instructed to take them if the mission was compromised during the bombing of Hiroshima.

Hiroshima Peace Flame will be lit till all nuclear bombs are destroyed. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park was built on the open field created by the explosion.

It is dedicated to the legacy of Hiroshima being the first city on earth to experience the horrors of a nuclear attack, and to the memories of the direct and indirect victims of the bombing. One of its monuments is the Peace Flame which was lit in 1964 and will continue to do so until all nuclear weapons on the planet are destroyed.

(Photo credit: US Army Archives / National Archives / Library of Congress).