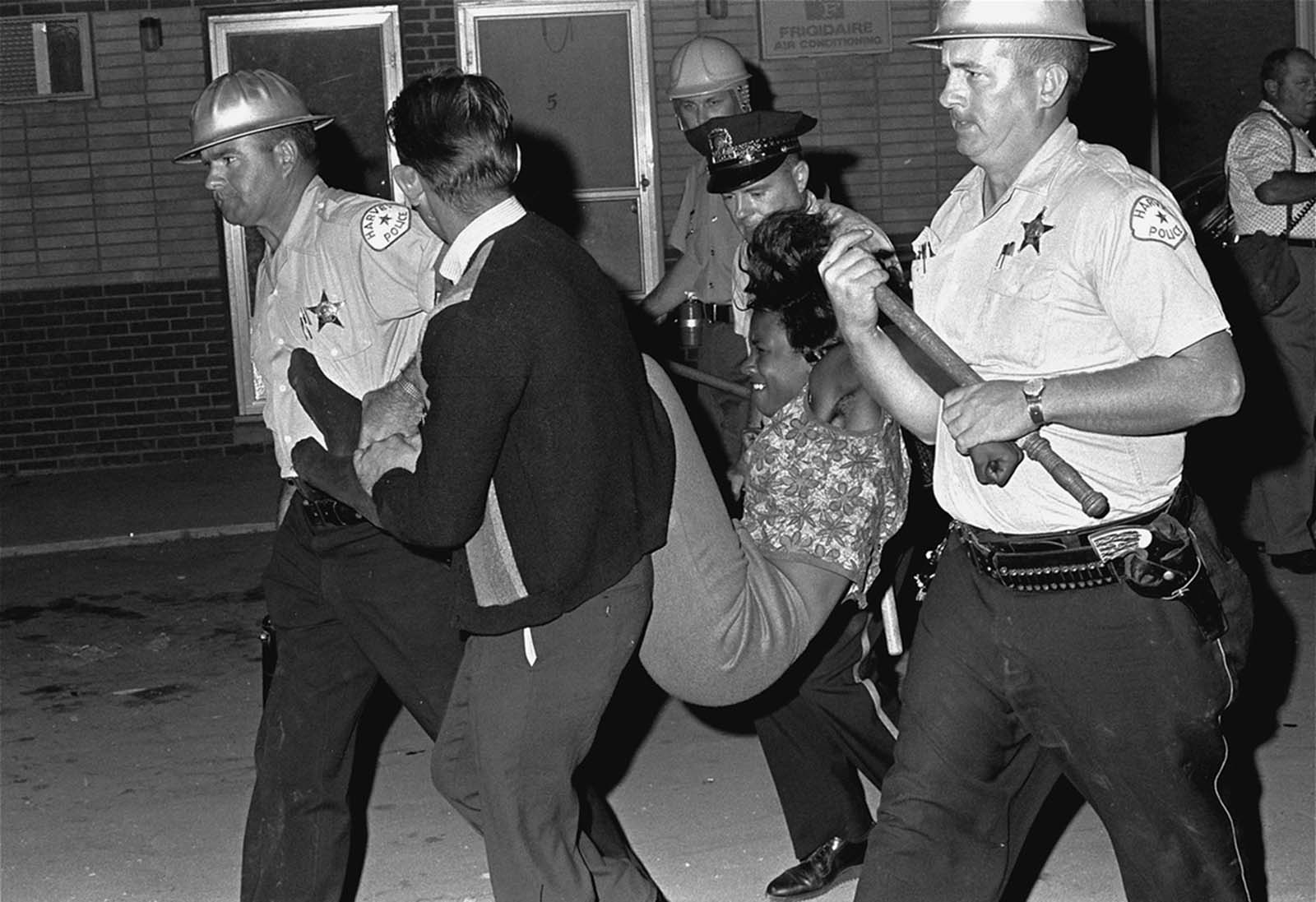

A woman who stayed at the riot scene in Dixmoor, IL, on August 17, 1964, is carried to a police van. Police had ordered all persons indoors in the race riot area. Those who didn’t were taken into custody in Dixmoor, a Chicago suburb. More than twelve were arrested. A number of large cities across the eastern U.S. experienced race-related riots during the summer of 1964.

Following World War II, pressures to recognize, challenge, and change inequalities for minorities grew.

One of the most notable challenges to the status quo was the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas which questioned the notion of “separate but equal” in public education.

The Court found that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and a violation of the 14th Amendment.

This decision polarized Americans, fostered debate and served as a catalyst to encourage federal action to protect civil rights.

In this January 18, 1964 photo, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, right, talks with civil rights leaders in his White House office in Washington. The black leaders, from left, are Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); James Farmer, national director of the Committee on Racial Equality; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and Whitney Young, executive director of the Urban League.

Each year, from 1945 until 1957, Congress considered and failed to pass a civil rights bill. Congress finally passed limited Civil Rights Acts in 1957 and 1960, but they offered only moderate gains.

As a result of the 1957 Act, the United States Commission on Civil Rights was formed to investigate, report on, and make recommendations to the President concerning civil rights issues.

Sit-ins, boycotts, Freedom Rides, the founding of organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, local demands for inclusion in the political process, all were in response to the increase in legislative activity through the 1950s and early 1960s.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gives a young protester a pat on the back as a group of youngsters started to picket St. Augustine, Florida, on June 10, 1964.

1963 was a crucial year for the Civil Rights Movement. Social pressures continued to build with events such as the Birmingham Campaign, televised clashes between peaceful protesters and authorities, the murders of civil rights workers Medgar Evers and William L. Moore, the March on Washington, and the deaths of four young girls in the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church.

There was no turning back. Civil rights were firmly on the national agenda and the federal government was forced to respond.

In response to the report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, President John F. Kennedy proposed, in a nationally televised address, the Civil Rights Act of 1963.

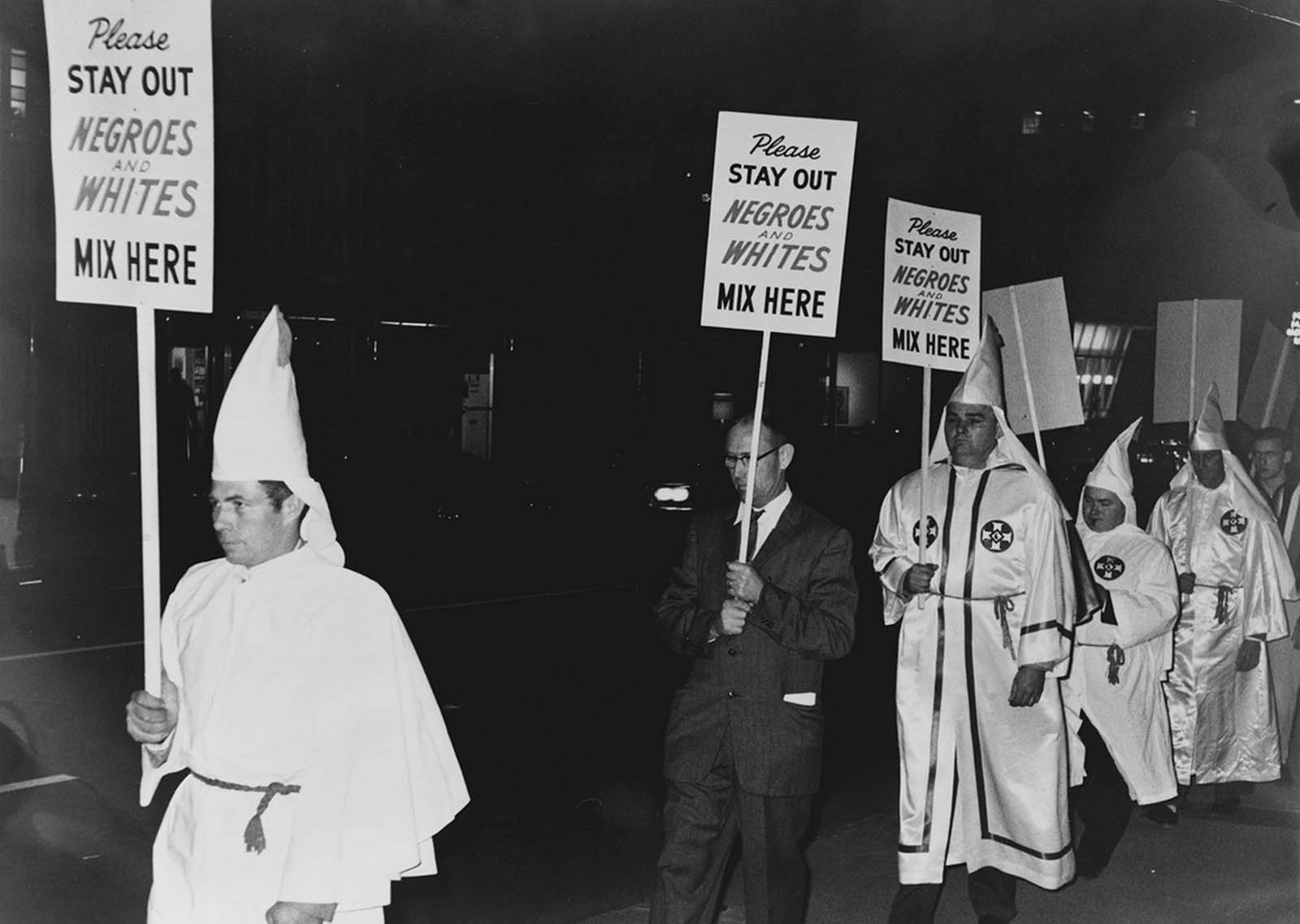

Several Ku Klux Klan members, most in white robes and unmasked hoods, carry placards stating: “Please stay out, Blacks and Whites mix here”.

A week after his speech, Kennedy submitted a bill to Congress addressing civil rights.

He urged African American leaders to use caution when demonstrating since new violence might alarm potential supporters.

Kennedy met with businessmen, religious leaders, labor officials, and other groups such as CORE and NAACP, while also maneuvering behind the scenes to build bipartisan support and negotiate compromises over controversial topics.

Ivory Ward, 43, sits in his car, with a hole in his windshield that he said was made by a bullet fired from a truck driven by white men, after African Americans marched in an integration demonstration, June 10, 1964, in St. Augustine, Florida.

Following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, both Martin Luther King, Jr. and newly inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson continued to press for passage of the bill.

King noted in a January 1964 newspaper column, the legislation “will feel the intense focus of Black interest… It became the order of the day at the great March on Washington last summer. The Black and his white compatriots for self-respect and human dignity will not be denied.”

The House of Representatives debated the civil rights bill for nine days, rejecting nearly 100 amendments designed to weaken the bill.

It passed the House on February 10, 1964, after 70 days of public hearings, appearances by 275 witnesses, and 5,792 pages of published testimony.

Integration demonstrators, after a long march through the white business and residential section of St. Augustine, Florida, held prayer sessions at the Monson Motor Lodge Restaurant on June 18, 1964, The restaurant has been the target of many sit-in attempts by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The real battle was waiting in the Senate, however, where concerns focused on the bill’s expansion of federal powers and its potential to anger constituents who might retaliate in the voting booth.

Opponents launched the longest filibuster in American history, which lasted 57 days and brought the Senate to a virtual standstill.

Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen nurtured the bill through compromise discussions and ended the filibuster. Dirksen’s compromise bill passed the Senate after 83 days of debate that filled 3,000 pages in the Congressional Record. The House moved quickly to approve the Senate bill.

A Toddle House restaurant in Atlanta, Georgia, occupied during a sit-in. In the room are Taylor Washington, Ivanhoe Donaldson, Joyce Ladner, John Lewis behind Judy Richardson, George Green, and Chico Neblett.

Within hours of its passage on July 2, 1964 President Lyndon B. Johnson, with Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Height, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, and other civil rights leaders in attendance, signed the bill into law, declaring once and for all that discrimination for any reason on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin was illegal in the United States of America.

Sit-in protests were held in cafes, restaurants, and hotels, opposing discriminatory service and hiring practices.

Small town all-white schools were required to integrate, and big-city schools began large-scale efforts to integrate by bus.

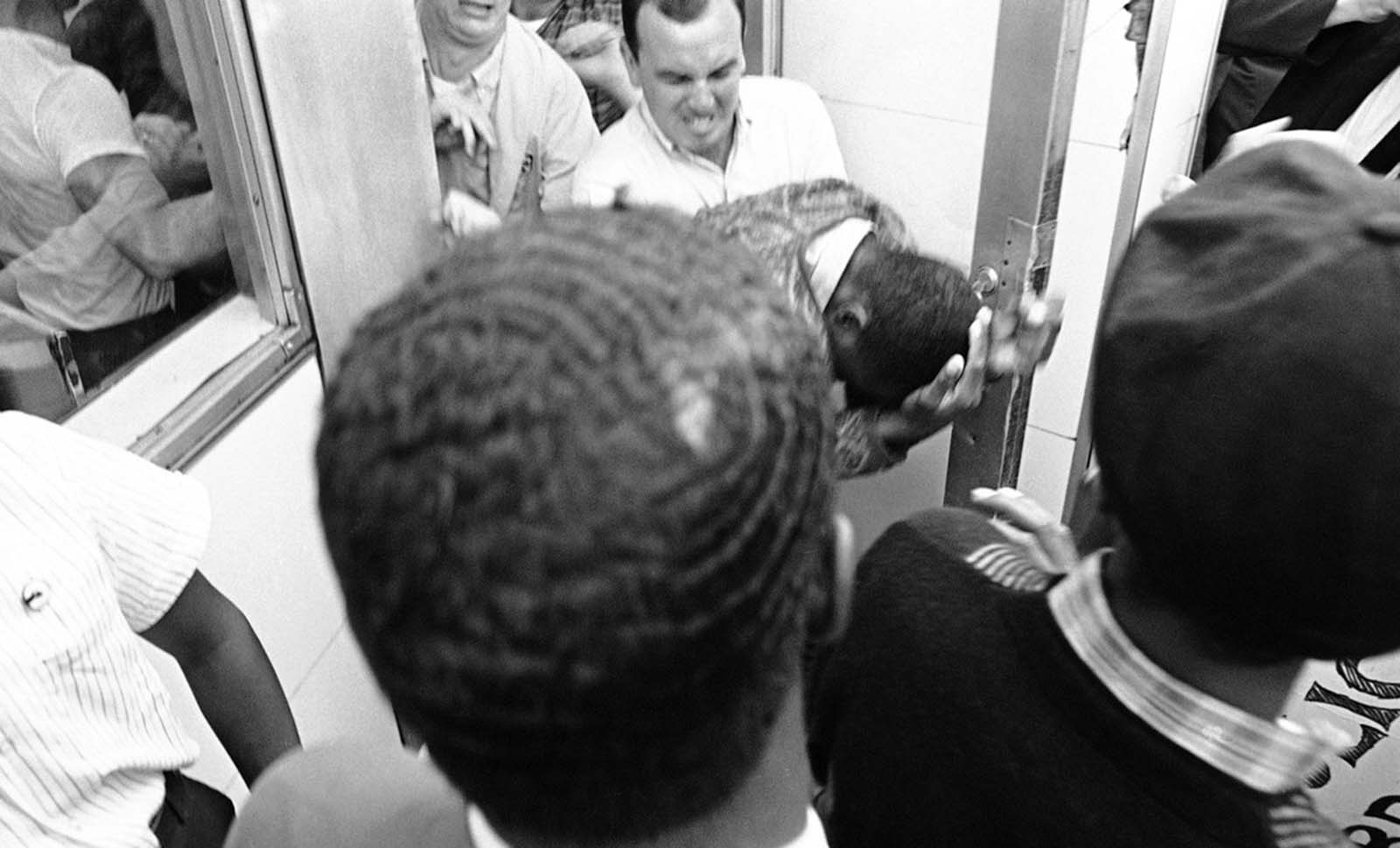

An unidentified African American demonstrator crouches for protection against blows from a white man in front of a segregated Nashville restaurant on May 1, 1964. Three or four African Americans were hurt in a series of scuffles between demonstrators and white men and white youths.

Segregationists, angered by the Civil Rights Act, took to the streets as well, often attacking African American demonstrations across the South.

Decades of police brutality, capped off by several incidents in the summer of 1964 led to a series of racially motivated riots in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Jersey City.

The year ended hopefully though, as activist Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was presented with the Nobel Peace Prize for his ongoing efforts to promote peaceful change amid harsh opposition and threats of violence.

Civil rights marchers walk through the streets of downtown Cambridge, Maryland, on May 12, 1964. The National Guard was deployed to keep order after a violent confrontation the night before.

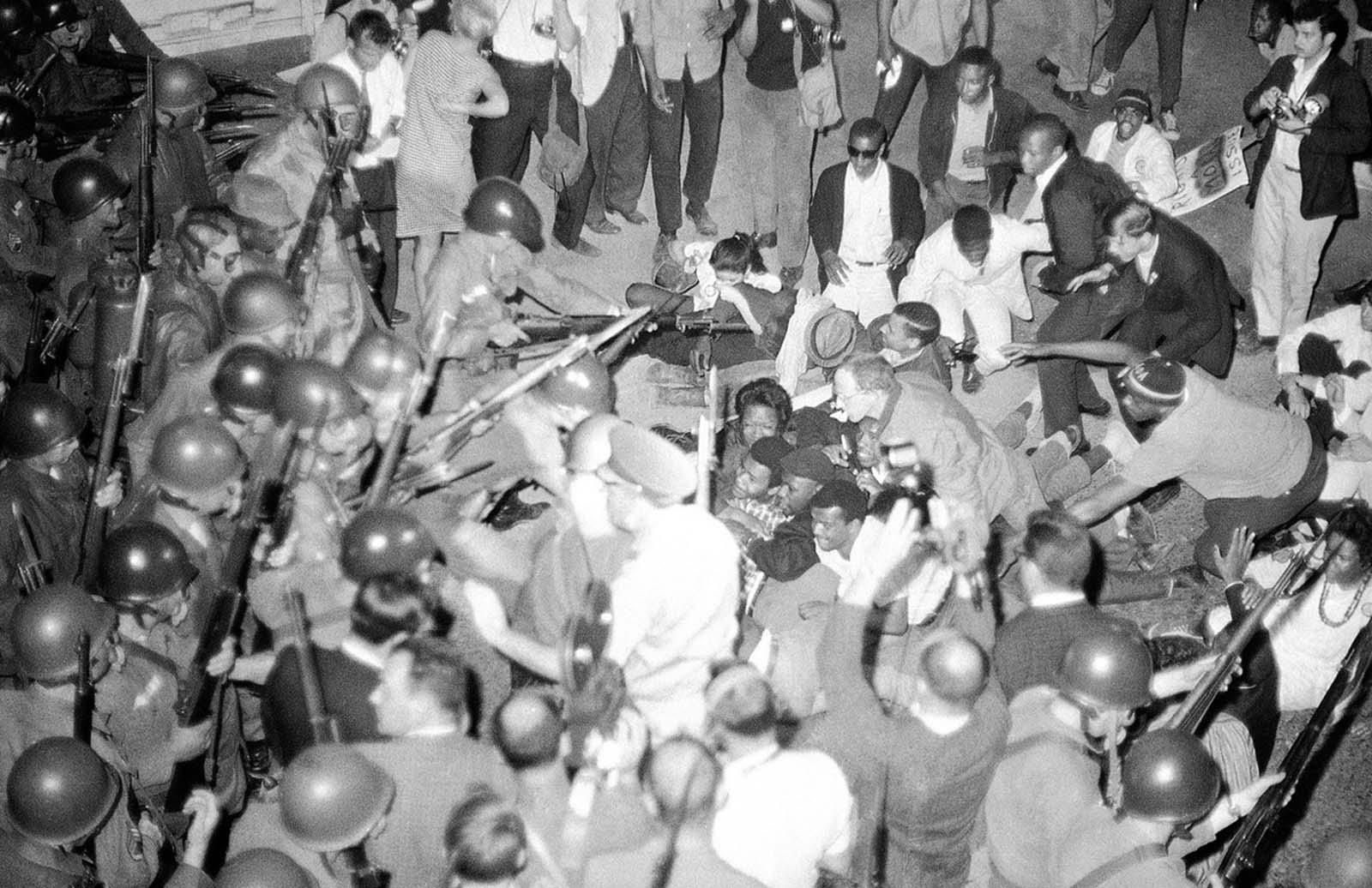

National Guard troops with upthrust bayonets surround integrationists kneeling in prayer as approximately 100 made a peaceful attempt to challenge the no-demonstration edict of the military commander in Cambridge, Maryland on May 13, 1964.

A police officer carrying a young girl walks past three civil rights demonstrators on the ground next to the Tulsa, Oklahoma, police station on April 2, 1964. The demonstrators were part of 54 arrested at a Tulsa restaurant. Members of the group, backed by the Congress of Racial Equality, went limp when arrested and forced officers to carry them from the restaurant and the paddy wagon.

J.B. Stoner, the segregationist from Atlanta, Georgia, holds a confederate flag as he addresses a large crowd of whites at a slave market in St. Augustine, Florida, on June 13, 1964, and then leads them on a long march through an African American residential section. On the right is a sign that read “Kill Civil Rights Bill.”

Andrew Young leans into a police car to talk to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the back seat with a police dog as he is returned to jail in St. Augustine, Florida, after testifying before a grand jury investigating racial unrest in the city on June 12, 1964.

New York City policemen tangle with demonstrators at a subway station on the opening day of the New York World’s Fair, April 22, 1964. Youths attempted to stall the train, which was headed from the city to the fairgrounds, as a form of protest on behalf of civil rights for blacks.

When a group of white and black integrationists refused to leave a motel swimming pool in St. Augustine, Florida, this man dove in and cleared them out on June 18, 1964. All were arrested.

When a group of white and African American integrationists entered a segregated hotel swimming pool, manager James Brock poured acid into it, shouting “I’m cleaning the pool!” in St. Augustine, Florida, on June 18, 1964. Read more about this picture.

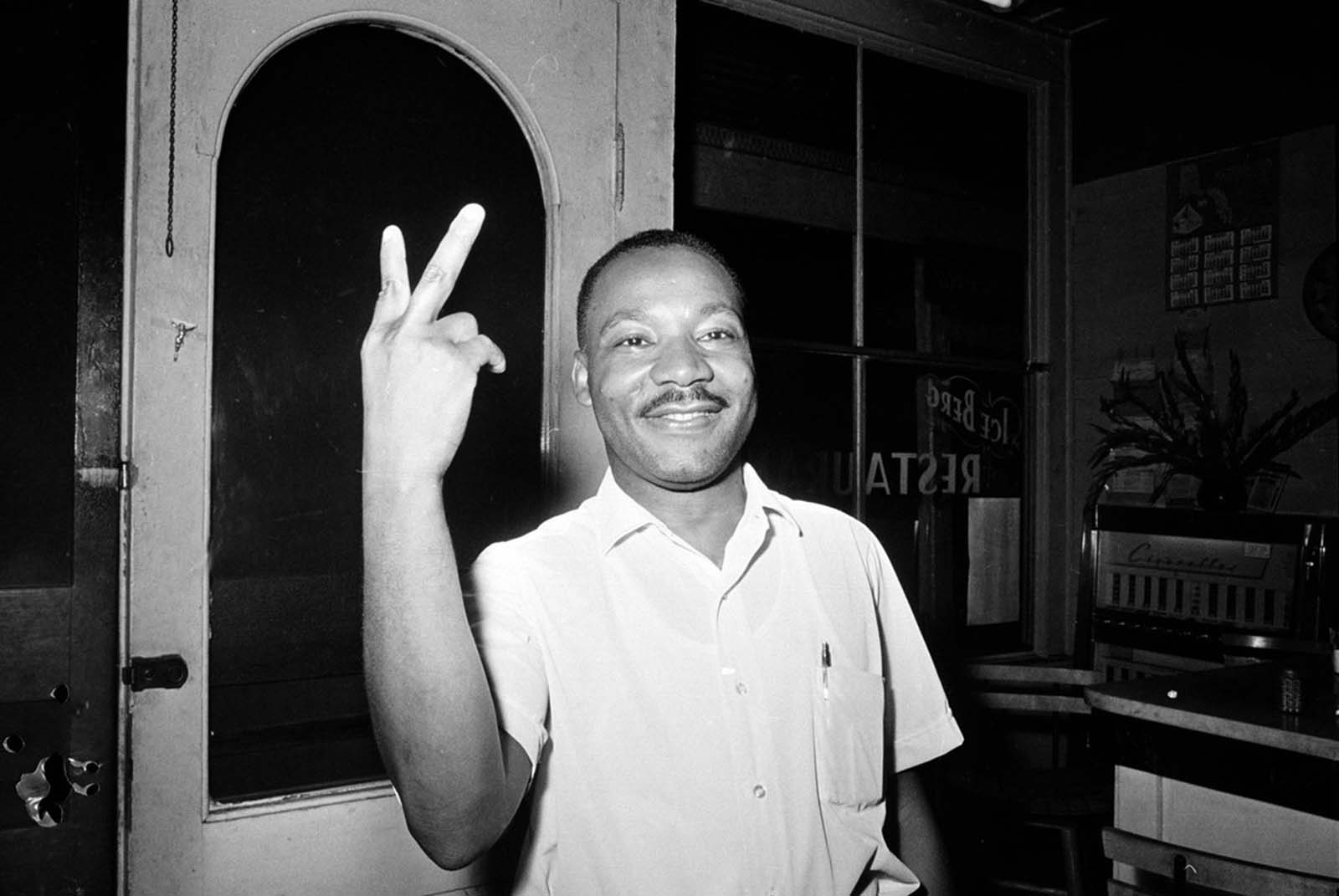

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in St. Augustine, Florida, reacts after learning that the U.S. Senate passed the civil rights bill on June 19, 1964.

The public swimming pool has been changed into a “private pool” in order to remain segregated, in Cairo, Illinois.

New York firemen, backed up by police, turn fire hoses on rioters in Rochester, New York, on July 25, 1964, in an effort to quell the street disturbance. Set off by reports of police brutality during an arrest on July 24, the Rochester riot lasted several days.

A police officer falls to the pavement as he struggles to apprehend a man in Rochester, New York, July 25, 1964.

This is the beginning of a clash between African Americans and police officers in Rochester, New York, on July 27, 1964. Fire hoses turned on the house’s porch. A woman stands her ground as companions duck behind the porch’s wall.

Police lead a man away during a clash in Rochester, New York, on July 27, 1964.

On June 29, 1964, the FBI began distributing these pictures of three missing civil rights workers, from left, Michael Schwerner, 24, of New York, James Chaney, 21, from Mississippi, and Andrew Goodman, 20, of New York, who disappeared near Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 21, 1964. The three civil rights workers, part of the “Freedom Summer” program, were abducted, killed, and buried by KKK members, in an earthen dam in rural Neshoba County.

Federal and State investigators recovered the station wagon of a missing civil rights trio in a swampy area near Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 29, 1964. The interior and exterior of the late model station wagon were heavily burned.

The Reverend Martin Luther King addresses a crowd estimated at 70,000 at a civil rights rally in Chicago’s Soldier Field, on June 21, 1964. King told the rally that congressional approval of civil rights legislation heralds “The dawn of a new hope for the N*gro.”

On July 15, 1964, a 15-year-old African American named James Powell was shot and killed by New York Police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan. The fatal shooting stirred rioters to race through Harlem streets carrying pictures of Gilligan, starting what would turn into six days of chaos, leaving one dead, 118 injured, and more than 450 arrested.

Members of New York’s Harlem community run from steel-helmeted police swinging nightsticks in an effort to break up street gathering on July 19, 1964. The mood of the crowd was ugly following demonstrations during the night from July 18 to 19 and funeral services on July 19 for James Powell.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Bill in the East Room of the White House in Washington on July 2, 1964. The law outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace, and by facilities that served the general public.

President Lyndon Johnson shakes hands with Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., on July 3, 1964, in Washington, District of Columbia, after handing him a pen during the ceremonies for the signing of the civil rights bill at the White House.

A state police officer with the club in hand overtakes a white segregationist, as African Americans attempted to swim and were attacked by a large group of whites at St. Augustine Beach, Florida, on June 25, 1964. The state police arrested a number of whites and African Americans.

A group of white segregationists attacks a group of blacks as they began to swim at St. Augustine Beach, Florida, on June 25, 1964. Police moved in and broke up the fighting.

A woman falls to the beach after she was attacked by three white women segregationists, when she attempted a wade-in with several African American and white desegregationist demonstrators at St. Augustine Beach, Florida, on June 23, 1964.

A group of African American and white demonstrators are guarded by a heavy surrounding force of police officers, during a wade-in at St. Augustine Beach, Florida, on June 29, 1964. Only a few segregationists were on hand and there were no incidents.

A man, his shirt stained by blood running down his face, is cornered in a doorway by club-wielding police early August 30, 1964, in North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The man had been clubbed for refusing to move along.

This view looking west from 15th Street on Columbia Ave. shows Main Street was involved in rioting in the predominantly black area of North Philadelphia during the previous night and continuing into August 29, 1964. At left, firemen clear smoldering rubble from the wrecked store. Demonstrators, bystanders, and police line the street in the background. Looting was widespread and damage-heavy. At least 50 persons were injured including 27 policemen.

Workmen move a cash register off the sidewalk in front of smashed store, wrecked during a wild night of looting and rioting in North Philadelphia, on August 29, 1964.

Two white students watch as African American children enter the previously all-white Rosewood Elementary School in Columbia, South Carolina, on August 31, 1964.

Holding their clubs in their hands, two Elizabeth policemen struggle with a man as they try to move him from the area of rioting in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on August 12, 1964. Police had to fire shots in the air and use their clubs to break up the crowd of 300 to 400 white and black youths tossing bricks, bottles, and gasoline bombs. It was the second night of violence in Elizabeth and Paterson, New Jersey.

An unidentified woman argues with a policeman in Paterson, New Jersey, on August 12, 1964, while a clergyman, center, tries to intervene.

A black youth who was shot either in the neck or shoulder during a flare-up of racial violence in Jersey City lies on a sidewalk while battle-helmeted policemen stand by to aid him on August 3, 1964. The youth, identified as Louis Mitchell, was among a group of young people standing near a housing project who were hurling objects at the police. It was not determined how the youth was shot. At least one other resident was shot and several police officers and rioters were injured in the outburst.

Demonstrators shout at policemen who ask them to move on along City Hall in New York, Sept. 24, 1964, as they protest a Board of Education busing program aimed at increasing racial balance in New York City schools.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. receives the Nobel Peace Prize from the hands of Gunnar Jahn, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, in Oslo, Norway, on December 10, 1964. The 35-year-old Reverend King was the youngest man ever to receive the prize. In the presentation speech, King was praised as a “man who has never abandoned his faith in the unarmed struggle he is waging, who has suffered for his faith, who has been imprisoned on many occasions, whose home has been subject to bomb attacks, whose life and the lives of his family have been threatened, and who nevertheless has never faltered.”

(Photo credit: AP Photo).