It was a moment in time that, even if you haven’t heard the story, you’ve probably seen the images.

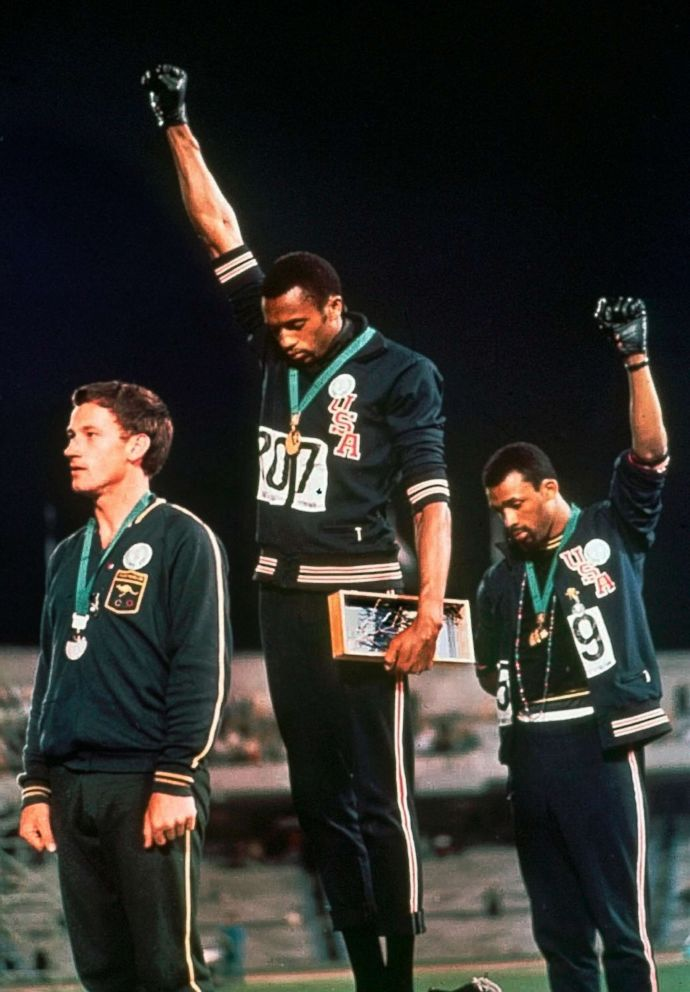

The date was Oct. 16, 1968, and Tommie Smith and John Carlos had just won the gold and bronze medals, respectively, at the Mexico City Summer Olympics. They had just finished the 200-meter sprint and earned the United States two spots on the medals podium.

But standing on the podium, the runners wore only their socks to shine a light on poverty in black communities. They wore clothing to protest lynchings — Smith a scarf, Carlos beads.

And with the national anthem playing in honor of their victories in the background, they dipped their heads and raised their fists — Smith his right, Carlos his left — each one covered in a black glove.

“It was probably the first and the most overt display of protest ever at the Olympic Games … It was very much revolutionary,” said Brad Congelio, assistant professor of sports management at Kutztown University, whose research focuses on the Olympic Games. “Using the Olympics as a way to show discontent goes completely against what Olympism is meant to stand for.”

Fifty years after Smith and Carlos stood on that podium, raising their fists in what some would call a black power salute, history seems to have come full circle in the actions of one man you’ve most likely heard of: former San Francisco 49ers star quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

“Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling is the exactly the same sort of symbolic protest as the black power salute from the 1968 Olympics,” said Leland Ware, who was in college at the time, and is now the Louis L. Redding Chair for the study of law and public policy at the University of Delaware.

“What’s ironic is the protest is for essentially the same thing as it was in 1968: racial oppression in America and the violence inflicted on African Americans by police,” Ware added. “It shows you that 50 years later, there have been some changes, but these issues are just as powerful now as they were then.”

The lead-up to the 1968 Olympics was fraught with chaos. The year before, nearly 160 riots broke out across the U.S. in what came to be known as the “long, hot summer of 1967.” The largest of the riots happened in Newark, while the most infamous was in Detroit, where 7,200 people had been arrested, 1,200 were injured and 43 killed.

Then, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, sparking a new wave of protests across the country.

“There were race riots in every major city in America,” Ware said.

Smith and Carlos were not the only athletes to wear symbols of protest during the Olympics, but they were the only ones to be castigated for it.

“As the anthem began and the crowd saw us raise our fists, the stadium became eerily quiet,” Carlos wrote in his 2011 book, “The John Carlos Story,” according to the Washington Post. “For a few seconds, you honestly could have heard a frog piss on cotton. There’s something awful about hearing 50,000 people go silent; like being in the eye of a hurricane.”

The men were ordered to leave the Olympic Village and forced to leave Mexico within 48 hours after their credentials were taken away, according to the New York Times.

Once home, they essentially had to start their careers from scratch as they were both banned from running track. After attempting to play in the NFL, Smith became a coach and Carlos a high school counselor, among other jobs the two had.

They also received hate mail, death threats and experienced harassment.

“They were racist, they were vile, and they were just disgusting displays of racism … But there were a handful of supporters, too,” Congelio said. “One of the supporters wrote that white Americans simply couldn’t understand the terrific agony that black Americans felt at the time … [they] just didn’t understand what [the athletes] were trying to prove and what their protest was about.”

Kaepernick, believed to be the first athlete to kneel during the national anthem, has also felt the blowback. He, too, has received death threats, according to ESPN.

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” he said, according to NFL News. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.”

“There are bodies in the street, and people are getting paid to leave and getting away with murder,” he said, referring to victims of police brutality — the reason he says he started the protest.

Kaepernick hasn’t played a game since the end of the 2016 season.

In the five decades since the Olympic protest, technology, of course, has advanced. In addition to the images of Kaepernick and like-minded athletes taking a knee being seen on televisions across the country, today’s demonstrators use social media as a tool.

“I think that social media allows athletes, to a certain degree, to take control of their own messaging, and counter these often negative stereotypes and misrepresentations, and directly challenge them,” Kaepernick said.

Despite not playing in the NFL for two years, Kaepernick has been able to capitalize on the movement he started. In early September, he was the face of Nike’s 30th anniversary “Just Do It” campaign.

By the end of the month, Nike’s market value had jumped an additional $6 billion, according to CBS, as crowds of people went to support the brand — and Kaepernick, of course.

Opponents of Kaepernick and other kneeling athletes, however, have burned their shoes and clothing to boycott the company.

It may have been more difficult 50 years ago to measure the impact of Smith’s and Carlos’ protests. But the Olympic stage put the athletes “in front of the eyes of the world,” Congelio said.

And their legacy speaks for itself, he added.

“Fifty years later, Smith and Carlos are largely looked back as civil rights heroes for what they did,” Congelio continued. “So 50 years from now, it’s going to be interesting to see if Kaepernick is seen the same way.”

On Thursday, Kaepernick received the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal from Harvard University for his contributions to black history and culture. In his speech, he encouraged more people with a platform to stand up against racial injustice.

“I feel like it’s not only my responsibility, but all our responsibilities as people that are in positions of privilege, in positions of power, to continue to fight for them and uplift them, empower them,” he said, according to USA Today. “Because if we don’t, we become complicit in the problem.”